The design and operation of cities is the province of urban planning. But an explosion of startups in cities means a lot of new products and services for urban areas. The problem is, we don’t really know how people are going to use these new products and services.

“The company launched a trial service in Santa Monica just last year and when I first saw the scooters (parked literally outside of our office) I was convinced nobody would want to ride them…The volume grew so steadily that I finally hopped on one, rode down to Bird’s offices and pleaded with Travis to take money from us. I had literally never seen a consumer phenomenon take off so quickly,” says Mark Suster in All The Questions You Wanted Answered about Bird Scooters and Their Recent $300 Million Funding.

There is no doubt Santa Monica scooter usage has benefited from a significant investment in bike lanes, as you can see from this map. If you doubt this, take a look at what happens as you travel a little outside of Santa Monica, where bike infrastructure doesn’t exist. Scooter riders take to sidewalks, just as they do on bikes. (I suspect data would also reveal less usage in these areas and that there are a lot of complaints in these areas about the scooters.)

Adapting To New Behavior

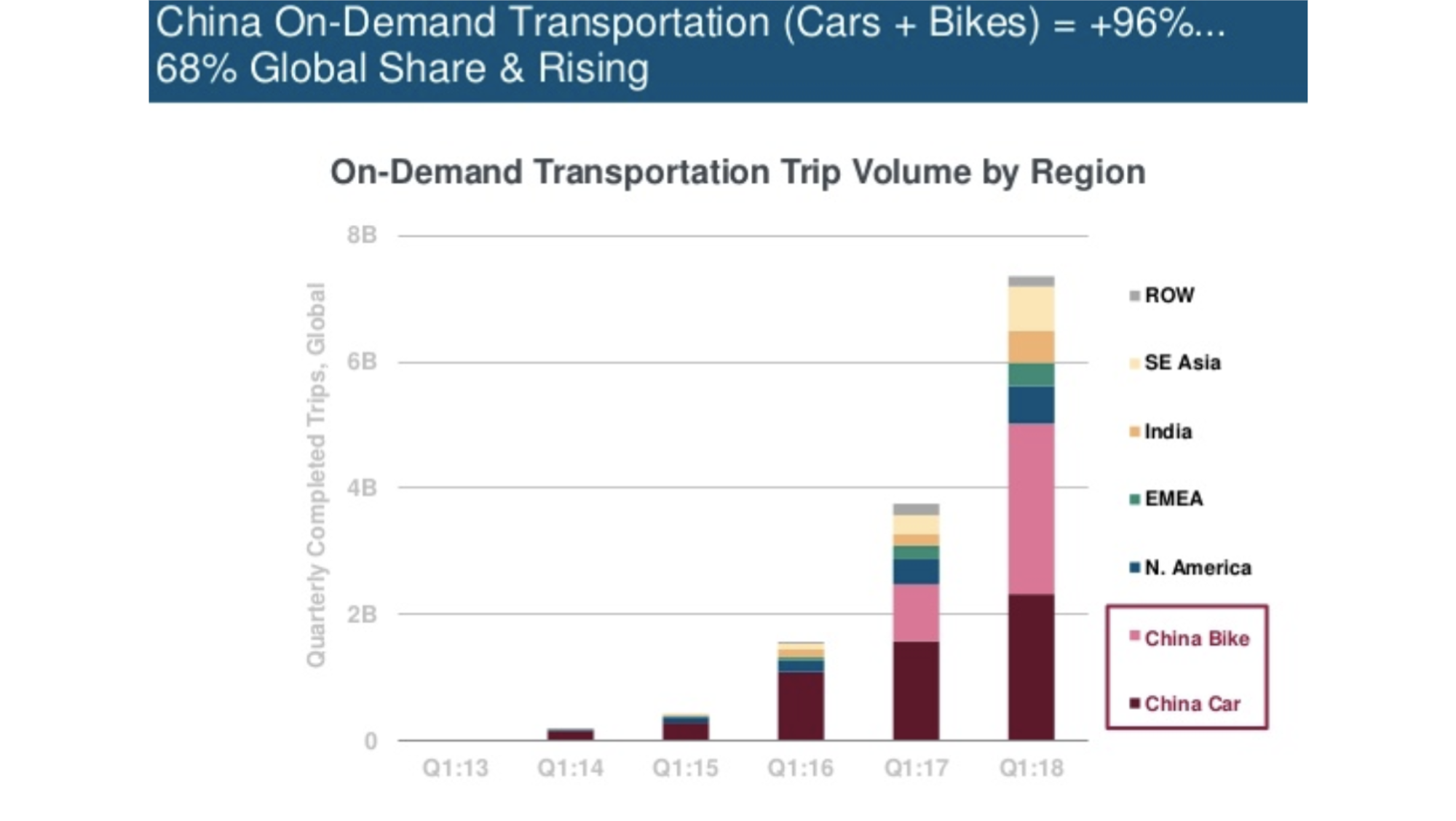

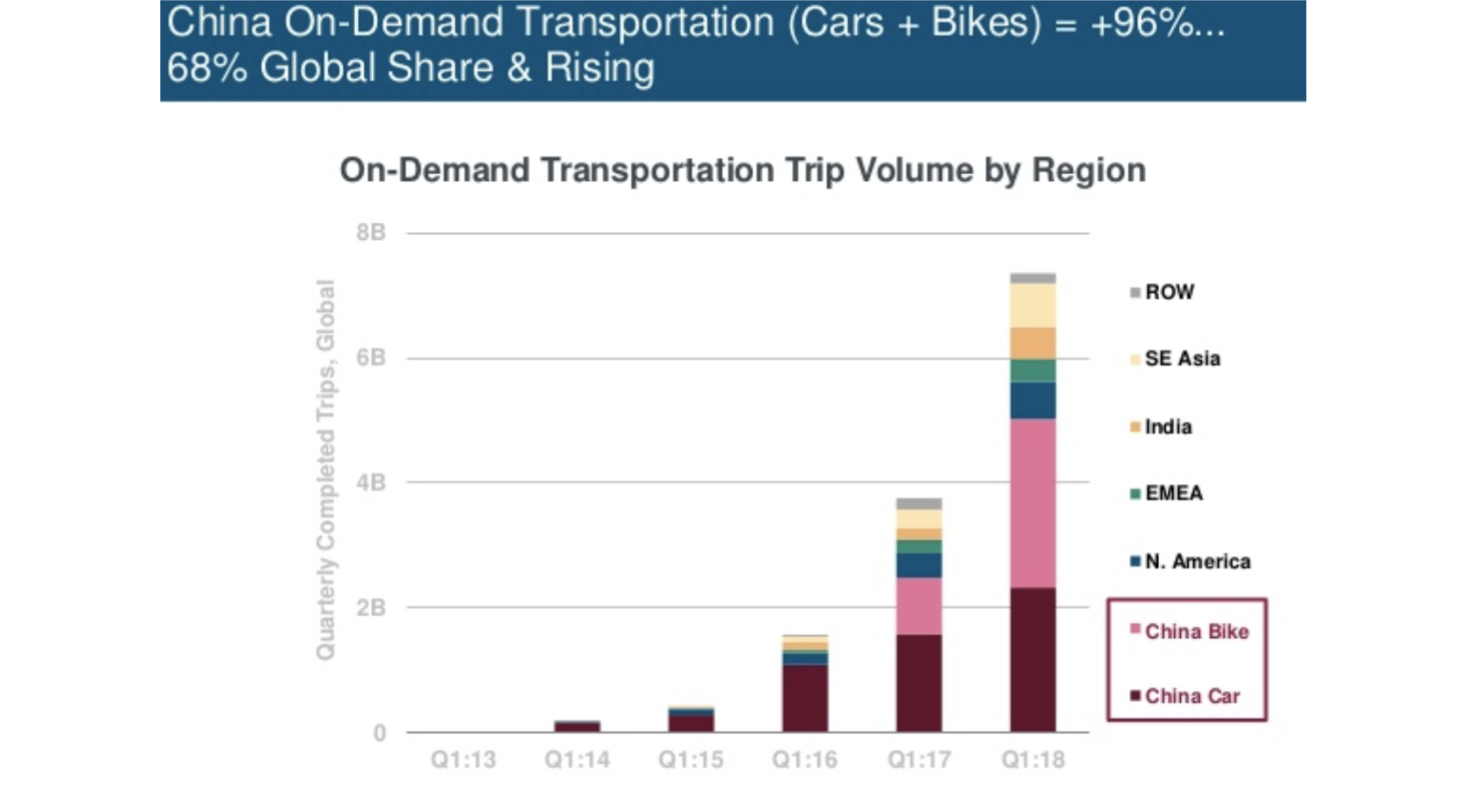

Just four-and-a-half years ago, people were stunned by the then huge valuation of Uber at over $3.5b. It took Uber just over four years to get to that valuation. Now Uber is acquiring electric, dockless bike companies and investing in shared scooters, as they dial back their self-driving activities. The chart below explains why.

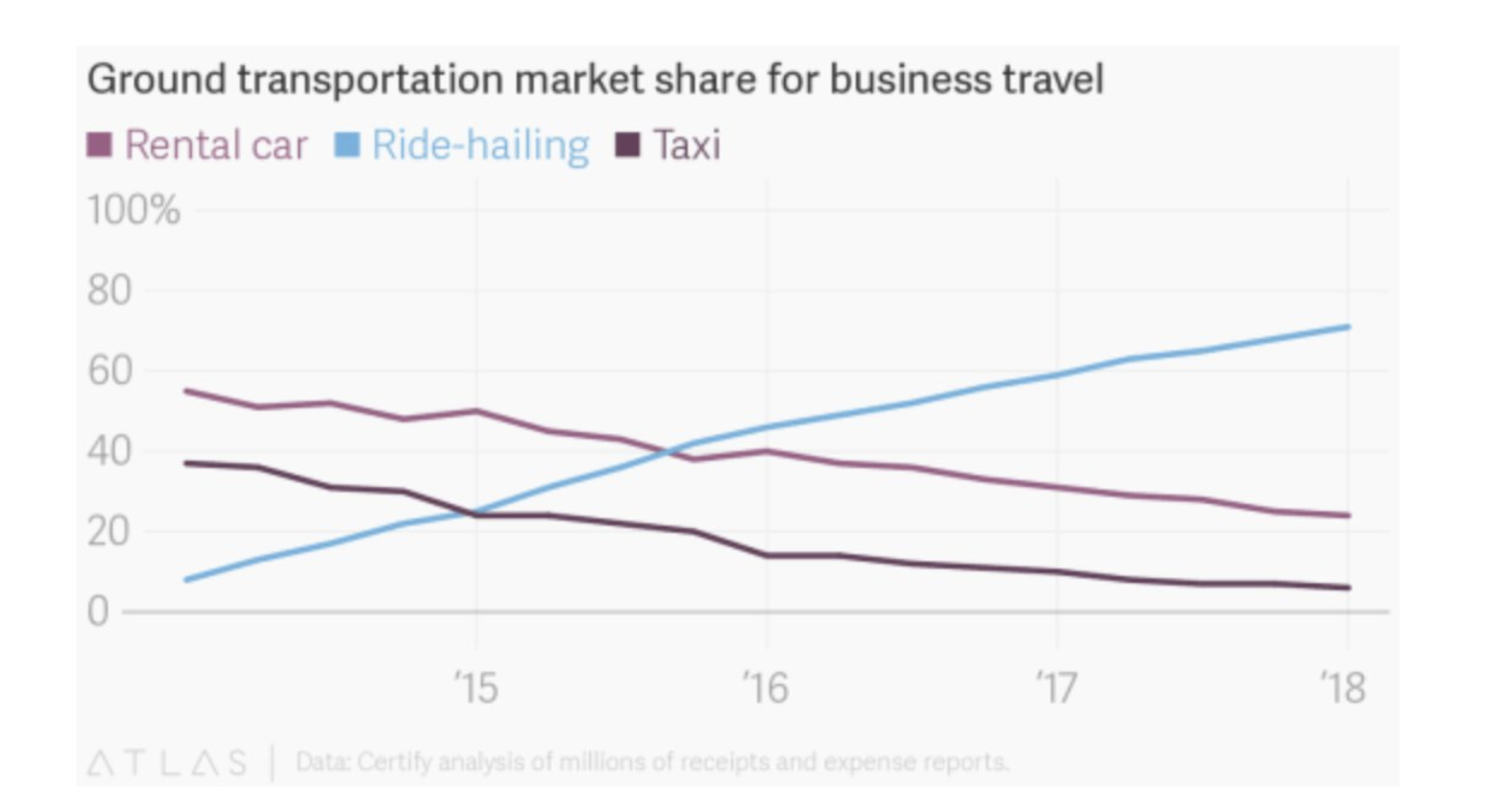

The practice of sharing rides came out of nowhere five years ago, and two years ago, docked bikeshare seemed to be rewriting what was possible with on-demand transportation. (Let’s see if/where scooters show up in Q1:19.) It’s hard to appreciate the impact of these new mobility models until you look at them against some well-established existing modes of transportation like taxis and car rentals. These industries trace their roots back to the explosion of the automobile with Model T’s a century ago and to when entrepreneurial companies like Hertz decided taxis should be yellow to enhance their visibility for hailing. (And yes, that’s the same yellow Hertz car rental sign.) As the chart below shows, these 100-year-old industries are rapidly melting away in the face of on-demand competition.

Revisiting City Planning

What does this mean for city planners? For a very long time in the US, cars have so dominated public spaces that we’ve mostly focused on parking and roads. e forget that companies lobbied for the car – they hadn’t always dominated public spaces, and now cities around the world are steadily pushing back. With new mobility options come new corporate alliances.

“San Francisco has more than 250,000 on-street parking spaces for “dockless” cars, so why does the addition of a few thousand dockless scooters spark such a heated debate?” says Roelof Botha, who is also an investor in Bird.

Parking for small shared EVs is just the start. What about the impact of last-mile options on public transit usage? Lyft’s “friends with transit” policy could be viewed cynically as a way to win favor with regulators, but last-mile trends are also playing out with smaller on-demand vehicles. In Germany, DB figured out the relationship between bikes and transit more than 10 years ago with the first dockless shared bikes, and the massive bike parking infrastructure connected to Dutch transit.

In the city most associated with car culture, you can now stop by any Metro station along the Expo Line in LA and see a growing number of bikes and scooters. Is this associated with an increase in transit usage? Is this another reason to sort out parking for small, last-mile vehicles? With more venture dollars in the mix, there are now strong alliances seeking to test new approaches.

Maybe We Just Forgot History

Just before cars finally took over most public spaces for transportation, there were more public transit options provided by some weirdly familiar looking vehicles. You can almost see how this 1922 Austro Motorette would eventually be given a seat to become the more familiar looking Vespa.

There are some important differences now. Electric vehicles need new charging infrastructure, which has led to debates about who will pay for it. On the other hand, scooter-sharing companies have learned infrastructure doesn’t need to look like charging stations. Small vehicles can have their batteries swapped out (as with the scooter- share Coup) or companies can offer incentives to people to take vehicles home to charge (and then return them). Electric vehicles will continue to drop in price as the main cost – batteries – become cheaper. Finally, shared vehicles have never been more available, and electric scooters are almost 100x cheaper than cars. What happens to behavior when availability is so high that it doesn’t require you to leave your block to find a vehicle.

Bad Old Assumptions

It seems inevitable that AVs will replace drivers at some point. While we wait for the takeover, there are some approaches we can take to improve safety. Unfortunately, some of these seem to have unintended negative consequences. Growing up I used to visit Zimbabwe, where speed bumps were called “sleeping policemen” because it was believed that they caused drivers to slow down and obey posted speed limits. But data from a recent NYU and Urban Us portfolio company Dash, reveal that “drivers have a tendency to accelerate quickly after traffic calming infrastructure like speed bumps, which can lead to dangerous situations for pedestrians.” This is potentially a new issue as more drivers discover previously quieter streets via navigation apps and it should still force us to revisit how we try to manage drivers who are going too fast.

Beyond Mobility

With NYC’s L train shutting down in 2019, people have started to plan their housing options and new commutes to and from Manhattan. The city has responded by saying they will add additional ferries and CitiBikes. But is there a way to add more options quickly? How might they fare in the winter? It’s hard to know, but the consequences go far beyond mobility to impact everything from restaurants to residential real estate.

Mobility ultimately has lot of consequences for real estate. Are people going to live in smaller private spaces in exchange for better shared amenities? Will they use robotic furniture to get more from smaller spaces? What might cause homeowners to purchase backup power in the form of a home battery system? How will this impact the grid? Will people be OK sharing sidewalks with delivery robots?

With so many questions about how our behavior will change, we need to find better, faster ways to test new solutions. Maybe alongside Departments of Urban Planning, we need Departments of Urban Testing.

Source: Tech Crunch