According to a report from Bloomberg, the Trump campaign called dibs on some of the most prized ad space online in the days leading up to the 2020 U.S. election.

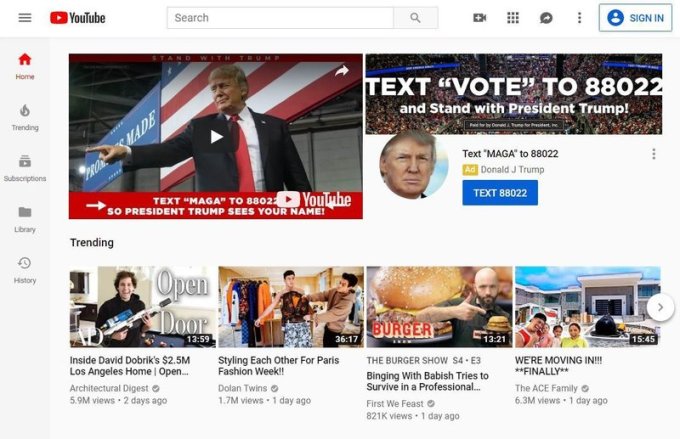

Starting in early November and continuing onto Election Day itself, the campaign will reportedly command YouTube’s masthead, the space at the very top of the video sharing site’s homepage. YouTube is now the second most popular website globally after the online video platform overtook Facebook in web traffic back in 2018. Bloomberg didn’t report the details of the purchase, but the YouTube masthead space is reported to cost as much as a million dollars a day.

The Trump campaign’s ad buy is likely to rub the president’s many critics the wrong way, but it isn’t unprecedented. In 2012, the Obama campaign bought the same space before Mitt Romney landed the Republican nomination. It’s also not a first for the Trump campaign, which bought banner ads at the top of YouTube last June to send its own message during the first Democratic debate.

Screenshot of the Trump campaign’s June 2019 YouTube ads via NPR/YouTube

In spite of the precedent, 2020 is a very different year for political money flowing to tech companies — one with a great degree of newfound scrutiny. The big tech platforms are still honing their respective rules for political advertising as November inches closer, but the kinks are far from ironed out and the awkward dance between politics and tech continues.

The fluidity of the situation is a boon to campaigns eager to plow massive amounts of cash into tech platforms. Facebook remains under scrutiny for its willingness to accept money for political ads containing misleading claims, even as the company is showered in cash by 2020 campaigns. Most notable among them is the controversial candidacy of multi-billionaire Mike Bloomberg, who spent a whopping $33 million on Facebook alone in the last 30 days. In spite of its contentious political ad policies, much-maligned Facebook offers a surprising degree of transparency around what runs on its platform through its robust political ad library, a tool that arose out of the controversy surrounding the 2016 U.S. election.

On the other end of the spectrum, Twitter opted to ban political ads altogether, and is currently working on a way to label “synthetic or manipulated media” intended to mislead users — an effort that could flag non-paid content by candidates, including a recent debate video doctored by the Bloomberg campaign. Twitter is working through its own policy issues in a relatively public way, embracing trial-and-error rather than carving its rules in stone.

Unlike Twitter, YouTube will continue to run political ads, but did mysteriously remove a batch of 300 Trump campaign ads last year without disclosing what policy the ads had violated. Google also announced that it would limit election ad targeting to a few high-level categories (age, gender and ZIP code), a decision the Trump campaign called the “muzzling of political speech.” In spite of its strong stance on microtargeting, Google’s policies around allowing lies in political ads fall closer to Facebook’s anything-goes approach. Google makes a few exceptions, disallowing “misleading claims about the census process” and “false claims that could significantly undermine participation or trust in an electoral or democratic process,” the latter of which leaves an amphitheater-sized amount of room for interpretation.

In recent years, much of the criticism around political advertising has centered around the practice of microtargeting ads to hyper-specific sets of users, a potent technique made possible by the amount of personal data collected by modern social platforms and a strategy very much back in action in 2020. While Trump’s campaign leveraged that phenomenon to great success in 2016, Trump’s big YouTube ad buy is just one part of an effort to see what sticks, advertising to anybody and everybody in the splashiest spot online in the process.

YouTube declined to confirm to TechCrunch the Trump campaign’s reported ad buy, but noted that the practice of buying the YouTube masthead is “common” during elections.

“In the past, campaigns, PACs, and other political groups have run various types of ads leading up to election day,” the spokesperson said. “All advertisers follow the same process and are welcome to purchase the masthead space as long as their ads comply with our policies.”

Source: Tech Crunch