Hello and welcome back to TechCrunch’s China Roundup, a digest of recent events shaping the Chinese tech landscape and what they mean to people in the rest of the world. The coronavirus outbreak is posing a devastating impact on people’s life and the economy in China, but there’s a silver lining that the epidemic might have benefited a few players in the technology industry as the population remains indoors.

The SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) virus that infected thousands and killed hundreds in China back in 2002 is widely seen as a catalyst for the country’s fledgling e-commerce industry. People staying indoors to avoid contracting the deadly virus flocked to shop online. Alibaba’s Taobao, an eBay-like digital marketplace, notably launched at the height of the SARS outbreak.

“Although it sickened thousands and killed almost eight hundred people, the outbreak had a curiously beneficial impact on the Chinese internet sector, including Alibaba,” wrote China internet expert Duncan Clark in his biography of Alibaba founder Jack Ma.

Nearly two decades later, as the coronavirus outbreak sends dozens of Chinese cities into various kinds of lockdown, tech giants are again responding to fill consumers’ needs amid the crisis. Others are providing digital tools to help citizens and the government battle the disease.

According to data from analytics company QuestMobile, Chinese people’s average time spent on the mobile internet climbed from 6.1 hours a day in January, to 6.8 hours a day during Chinese New Year, to an astounding daily usage of 7.3 hours post-holiday as businesses delay returning to the office or resuming on-premises operation.

Here’s a look at what some of them are offering.

Remote work apps: Boom and crash

China’s enterprise software industry has been slow to take off in comparison to the West, though it’s slowly picking up steam as the country’s consumer-facing industry becomes crowded, prompting investors and tech behemoths to bet on more business-oriented services. Now remote work apps are witnessing a boom as millions are confined to working from home.

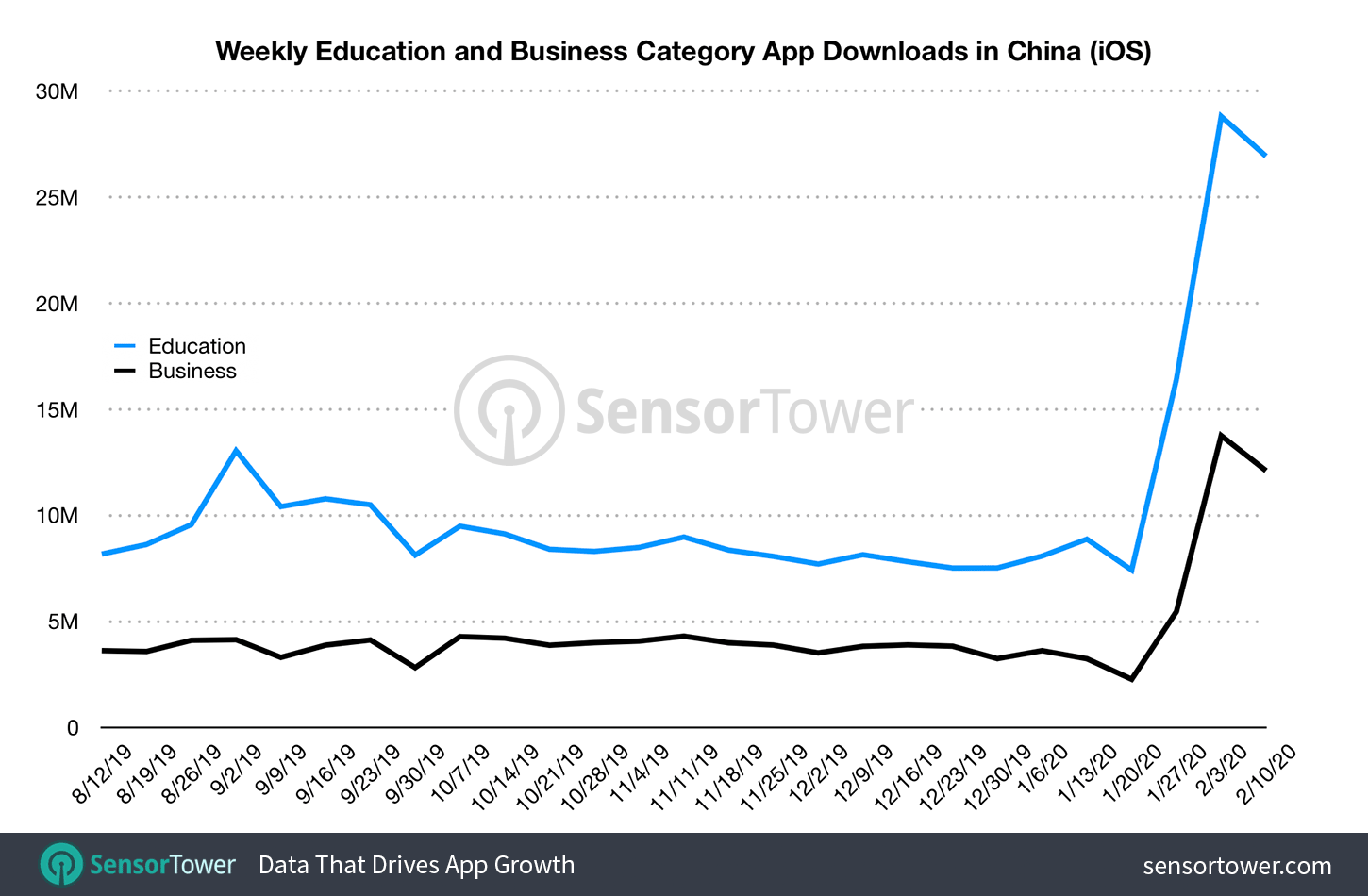

The online education sector is experiencing a similar uptick as schools nationwide are suspended, according to data from research firm Sensor Tower.

The main players trying to tap the nationwide work-from-home practice are Alibaba’s DingTalk, Tencent’s WeChat Work, and ByteDance’s Lark. App rankings compiled by Sensor Tower show that all three apps experienced significant year-over-year growth in downloads from January 22 through February 20, though their user bases vary greatly:

DingTalk: 1,446%

Lark: 6,085%

WeChat Work: 572%

DingTalk, launched in 2014 by an Alibaba team after its failed attempt to take on WeChat, shot up to the most-downloaded free iOS app in China in early February. The app claimed in August that more than 10 million enterprises and over 200 million individual users had registered on its platform.

Dingtalk became China’s most-downloaded free iOS app mid the coronavirus outbreak. Data: Sensor Tower

WeChat’s enterprise version WeChat Work, born in 2016, trailed closely behind DingTalk, rising to second place among free iOS apps in the same period. In December, WeChat Work announced it had logged more than 2.5 million enterprises and some 60 million active users.

Lark, launched only in 2019, pales in comparison to its two predecessors, hovering around the 300th mark in early February. Nonetheless, Lark appears to be making a big user acquisition push recently by placing ads on its sibling Douyin, TikTok’s China version. Douyin has emerged as a marketing darling as advertisers rush to embrace vertical, short videos, and Lark can certainly benefit from exposure on the red-hot app. WeChat, despite its colossal one-billion monthly user base, has remained restrained in ad monetization.

The question is whether the sudden boom will develop into a sustainable growth trend for these apps. System crashes on DingTalk and WeChat Work due to user influx at the start of the remote working regime might suggest that neither had projected such traffic volumes on its growth curve. After all, most businesses are expected to resume in-person communication when safety conditions are ensured.

Indeed, the work-from-home model has been widely ill-received by employees who are frustrated with intrusive company rules like “keep your webcam on while working from home.” In a more unexpected turn, DingTalk suffered from a backlash after it added tools to host online classes for students. Resentful that the app had spoiled their extended holiday, young users flooded to give DingTalk one-star ratings.

Face mask algorithms

To curb the spread of the virus, local governments in China have mandated people to wear masks in public, posing a potential challenge to the country’s omnipresent facial recognition-powered identity checks. But the technologies necessary to handle the situation is already in place, such as iris scanning.

Travelers whom I spoke to reported they are now able to pass through train station security without taking their masks off — which could sound an alarm to privacy-conscious individuals. But it’s unclear whether the change is due to more advanced forms of biometrics technologies or that the authority had temporarily loosened security on low-risk individuals. People still have to scan their ID cards before getting their biometrics verified and travelers whose identities have been flagged could trigger stricter screening, people familiar with China’s AI industry told me. They added that the latter case is more probable, for it will take time to implement a nationwide infrastructure upgrade.

Digital passes

Local governments have also introduced tools for people to attain digital records of their travel history, which has become some sort of permit to go about their daily life, be it returning to work, their apartment, or even the city they live in.

One example is web-based app Close Contact Detector developed by a state-owned company. Users can obtain a record of their travel history by opting to submit their names, ID numbers and phone numbers. So far the app has drawn more scorn than praise for containing the virus, bringing people to the questions: If the government already has a grip on people’s travel history, why didn’t it react earlier to restrict the free flow of travelers? Why did it only introduce the service a few weeks after the first big outbreak?

All of this could point to the challenge of collecting and consolidating citizen data across departments and regions, despite China’s ongoing efforts to encourage the use of social credits nationwide through the use of real-name registration and big data. The health crisis appears to have accelerated this data-unification process. The pressing question is how the government will utilize these data following the outbreak.

Many of these digital permits are powered by WeChat on the merit of the messenger’s ubiquity and broad-ranging functions in Chinese society. In Shenzhen, where WeChat’s parent Tencent is headquartered, cars can only enter the city after the drivers use WeChat to scan a QR code hung by a drone — for the obvious reason to avoid contact with checkpoint officers — and digitally file their travel history.

Photo: Xinhua News

Citizen reporting

As the fast-spreading virus fuels rumors, individual citizens are playing an active role in combating misinformation. Dxy.cn (丁香园), an online community targeting medical professionals, responded swiftly with a fact-checking feature dedicated to the coronavirus and a national map tracking the development of the outbreak in real time.

Yikuang, the brainchild of several independent developers and app review site Sspai.com, is one of the first WeChat-based services to map neighborhoods with confirmed cases using official data from local governments.

Young citizens have also joined in. A Shanghai-based high school senior and his peers launched a blog that provides Chinese summaries of coronavirus coverage from news organizations around the world.

Dining and entertainment

The nationwide lockdown is almost guaranteed a boon to online entertainment. The short video sector recorded 569 million daily active users in the post-holiday period, far exceeding 492 million on a regular daily basis, shows QuestMobile. Video streaming sites are gathering musicians to virtually perform and movies are premiering online as the virus forces live venues and cinemas to shut.

Many Chinese cities have gone as far as to ban eating in restaurants during the epidemic, putting the burden on food and grocery delivery services. To ensure safety, delivery companies have devised ways to avoid human interaction, such as Meituan Dianping’s “contactless” solution, which is in effect a self-served cabinet to temporarily store food orders awaiting customer pickup.

Source: Tech Crunch