Shahin Farshchi

Contributor

More posts by this contributor

I entered the world of venture investing a dozen years ago. Little did I know that I was embarking on a journey to master the art of balancing contradictions: building up experience and pattern recognition to identify outliers, emphasizing what’s possible over what’s actual, generating comfort and consensus around a maverick founder with a non-consensus view, seeking the comfort of proof points in startups that are still very early, and most importantly, knowing that no single lesson learned can ever be applied directly in the future as every future scenario will certainly be different.

I was fortunate to start my venture career at a fund specializing in funding “Frontier” technology companies. Real-estate was white hot, banks were practically giving away money, and VCs were hungry to fund hot startups.

I quickly found myself in the same room as mainstream software investors looking for what’s coming after search, social, ad-tech, and enterprise software. Cleantech was very compelling: an opportunity to make money while saving our planet. Unfortunately for most, neither happened: they lost their money and did little to save the planet.

Fast forward a decade, after investors scored their wins in online lending, cloud storage, and on-demand, I find myself, again, in the same room with consumer and cloud investors venturing into “Frontier Tech”. The are dazzled by the founders’ presentations, and proud to have a role in funding turning the seemingly impossible to what’s possible through science. However, what lessons did they take away from the Cleantech cycle? What should Frontier Tech founders and investors be thinking about to avoid the same fate?

Coming from a predominantly academic background, I was excited to be part of the emerging trend of funding founders leveraging technology to make how we generate, move, and consume our natural resources more efficient and sustainable. I was thrilled to be digging into technologies underpinning new batteries, photovoltaics, wind turbines, superconductors, and power electronics.

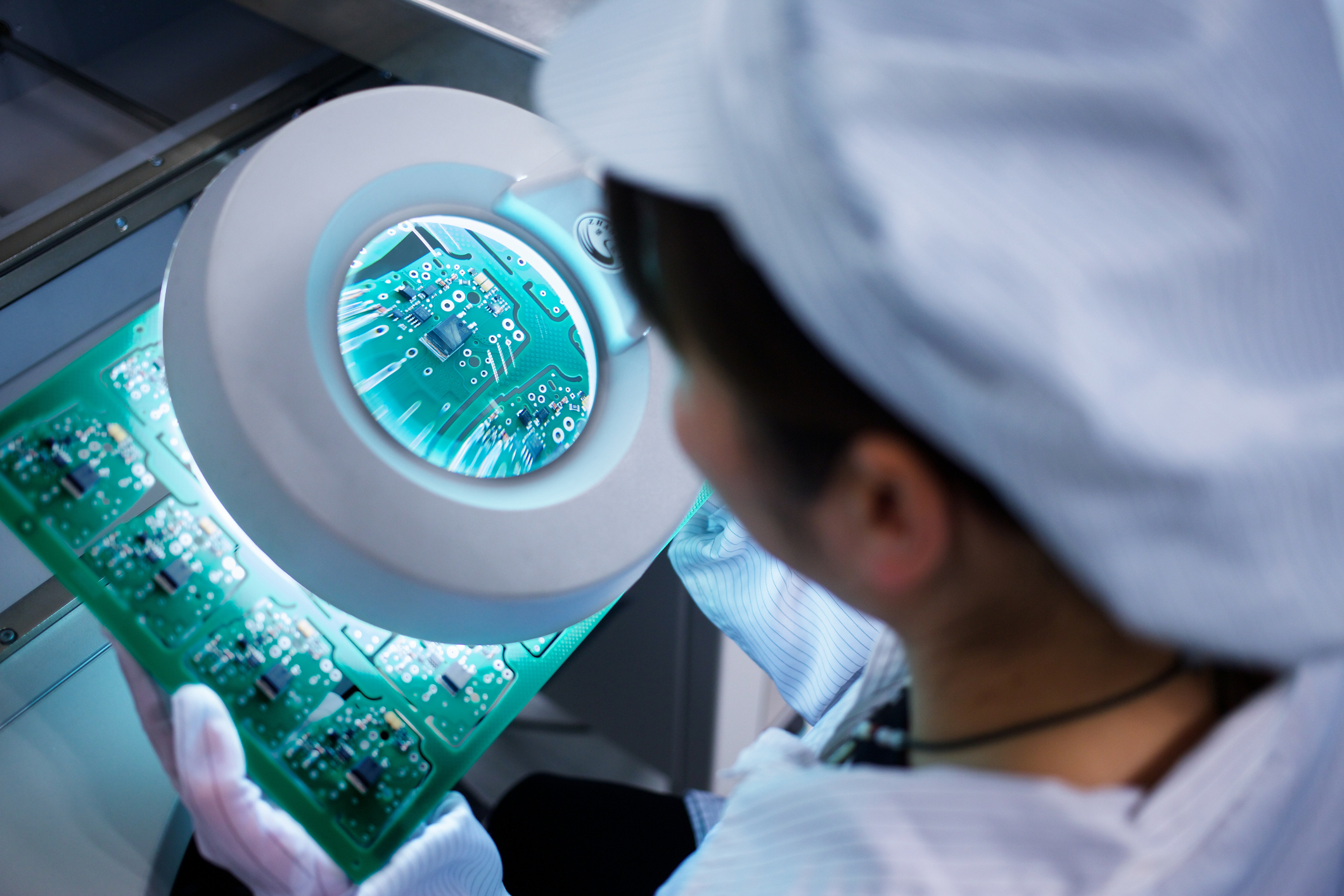

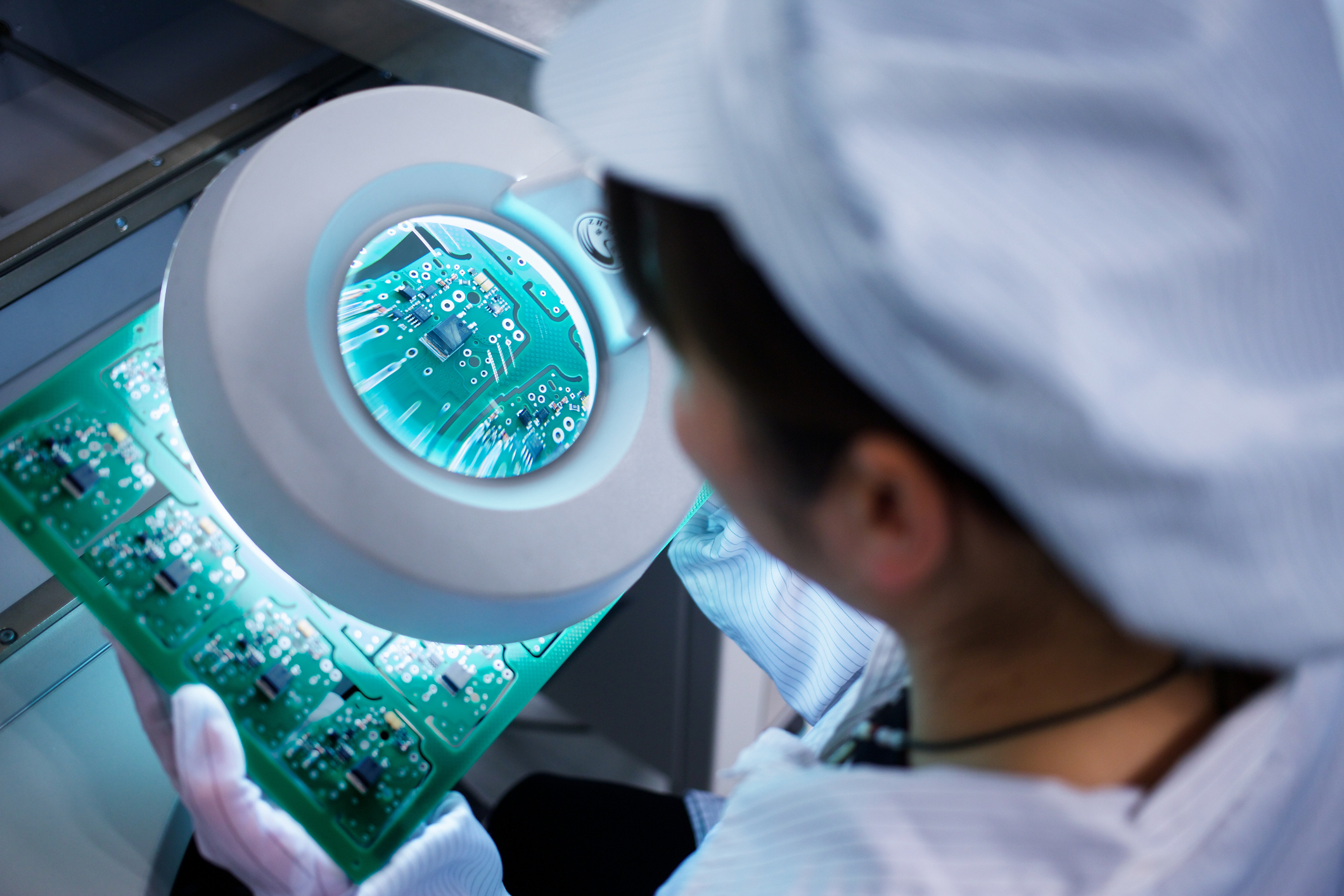

To prove out their business models, these companies needed to build out factories, supply chains, and distribution channels. It wasn’t long until the core technology development became a small piece of an otherwise complex, expensive operation. The hot energy startup factory started to look and feel mysteriously like a magnetic hard drive factory down the street. Wait a minute, that’s because much of the equipment and staff did come from factories making components for PCs; but this time they were making products for generating, storing, and moving energy more renewably. So what went wrong?

Whether it was solar, wind, or batteries, the metrics were pretty similar: dollars per megawatt, mass per megawatt, or multiplying by time to get dollars and mass per unit energy, whether it was for the factories or the systems. Energy is pretty abundant, so the race was on to to produce and handle a commodity. Getting started as a real competitive business meant going BIG: as many of the metrics above depended on size and scale. Hundreds of millions of dollars of venture money only went so far.

The onus was on banks, private equity, engineering firms, and other entities that do not take technology risk, to take a leap of faith to take a product or factory from 1/10th scale to full-scale. The rest is history: most cleantech startups hit a funding valley of death. They need to raise big money while sitting at high valuations, without a kernel of a real business to attract investors that write those big checks to scale up businesses.

How are Frontier-Tech companies advantaged relative to their Cleantech counterparts? For starters, most aren’t producing a commodity…

Frontier Tech, like Cleantech, can be capital-intense. Whether its satellite communications, driverless cars, AI chips, or quantum computing; like Cleantech, there is relatively larger amounts of capital needed to take the startups the point where they can demonstrate the kernel of a competitive business. In other words, they typically need at least tens of millions of dollars to show they can sell something and profitably scale that business into a big market. Some money is dedicated to technology development, but, like cleantech a disproportionate amount will go into building up an operation to support the business. Here are a couple examples:

- Satellite communications: It takes a few million dollars to demonstrate a new radio and spacecraft. It takes tens of millions of dollars to produce the satellites, put them into orbit, build up ground station infrastructure, the software, systems, and operations needed to serve fickle, enterprise customers. All of this while facing competition from incumbent or in-house efforts. At what point will the economics of the business attract a conventional growth investor to fund expansion? If Cleantech taught us anything, it’s that the big money would prefer to watch from the sidelines for longer than you’d think.

- Quantum compute: Moore’s law is improving new computers at a breakneck pace, but the way they get implemented as pretty incremental. Basic compute architectures date back to the dawn of computing, and new devices can take decades to find their way into servers. For example, NAND Flash technology dates back to the 80s, found its way into devices in the 90s, and has been slowly penetrating datacenters in the past decade. Same goes for GPUs; even with all the hype around AI. Quantum compute companies can offer a service direct to users, i.e., homomorphic computing, advanced encryption/decryption, or molecular simulations. However, that would one of the rare occasions where novel computing machine company has offered computing as opposed to just selling machines. If I had to guess; building the quantum computers will be relatively quick; building the business will be expensive.

- Operating systems for driverless cars: Tremendous progress has been made since Google first presented its early work in 2011. Dozens of companies are building software that do some combination of perception, prediction, planning, mapping, and simulations. Every operator of autonomous cars, whether they are vertical like Zoox, or working in partnerships like GM/Cruise, have their own proprietary technology stacks. Unlike building an iPhone app, where the tools are abundant and the platform is well-understood, integrating a complete software module into an autonomous driving system may take up more effort than putting together the original code in the first place.

How are Frontier-Tech companies advantaged relative to their Cleantech counterparts? For starters, most aren’t producing a commodity: it’s easier to build a Frontier-tech company that doesn’t need to raise big dollars before demonstrating the kernel of an interesting business. On rare occasions, if the Frontier tech startup is a pioneer in its field, then it can be acquired for top dollar for the quality of its results and its team.

Recent examples are Salesforce’s acquisition of Metamind, GM’s acquisition of Cruise, and Intel’s acquisition of Nervana (a Lux investment). However, as more competing companies get to work on a new technology, the sense of urgency to acquire rapidly diminishes as the scarce, emerging technology quickly becomes widely available: there are now scores of AI, autonomous car, and AI chip companies out there. Furthermore, as technology becomes more complex, its cost of integration into a product (think about the driverless car example above) also skyrockets. Knowing this likely liability, acquirers will tend to pay less.

Creative founding teams will find ways to incrementally build interesting businesses as they are building up their technologies.

I encourage founders, and investors to emphasize the businesses they are building through their inventions. I encourage founders to rethink plans that require tens of millions of dollars before being able to sell products, while warning founders not to chase revenue for the sake of revenue.

I suggest they look closely at their plans and find creative ways to start penetrating, or building exciting markets, hence interesting businesses, with modest amounts of capital. I advise them to work with investors who, regardless of whether they saw how Cleantech unfolded, are convinced that their $$ can take the company to the point where it can engage customers with an interesting product with a sense for how it can scale into an attractive business.

Source: Tech Crunch