Shaun Abrahamson

Contributor

More posts by this contributor

Portfolio co-founder: Our other investors want to participate but our lead wants to take most of the round.

Me: OK

Portfolio co-founder: So that means pro-rata is going to be tough.

Me: Let’s see what everyone says.

A few days later.

Portfolio co-founder: The math worked out. Some people didn’t do their pro-rata and others did more.

Me: In theory, this shouldn’t happen because everyone is doing their pro-rata, but this is usually how things seem to work out. The round wasn’t going to be put at risk over pro-rata.

We’re always curious to see how rounds come together when there is limited capacity for both new investors and existing investor pro-rata. For the most part, there is supposed to be one core investor strategy; the maintainers, who use reserves and then opportunity funds or SPVs to avoid or minimize dilution. Sometimes there are also accumulators, who use multiple rounds to expand their ownership, but this is more common in private equity outside of venture capital.

The maintainers are pretty well understood. They have the typical $1 in reserve for each $1 invested, mirroring a common strategy espoused by some of the best VCs. USV shared a great example including fund allocation assumptions. Accumulators are a little more surprising to meet, but Greenspring, which is uniquely positioned to observe a lot of early-stage managers, hint that one of their top performing managers uses the accumulator strategy to get to more than 20 percent, fully diluted at exit. That’s not the whole story though, because, unlike USV, the strategy also involves some additional important assumptions, most notably investing in less-competitive geographies.

We’ve seen other allocation strategies, but we don’t see a lot written about them. For example, some investors tend to be among the first checks and, going through our co-investments with them, it’s clear they don’t always take pro-rata, but don’t seem to fuss about it. Here’s a great example of how one of today’s very best seed-stage investors, Founder Collective, thinks about this:

We dilute alongside our founders over time. So we have the same incentives as our founders to increase the value of the company in future financings.

It’s easy to dismiss this as founder-friendly at the expense of LPs, but I suspect Founder Collective’s LPs don’t see it that way at all. It’s hard to know how often this positioning leads to a higher win rate on competitive deals, but let’s assume there is little difference. Does the math work?

Let’s assume a VC is buying 20 percent of the company and then riding the dilution train down to a fully diluted 5.2 percent on exit at Series F (thanks to Fred Wilson again; in this example, we’re using one of his recent frameworks with these exact numbers). For a $50 million fund, this works just fine. Interestingly, it looks similar to the result for a $100 million fund with reserves, but the later assumes that they can always secure pro-rata and they can make use of opportunity funds to get a bit more upside.

We’ve discussed this a lot as we deployed our last fund. The vast majority of people insisted we needed $1 for every $1 invested, but we found that, thanks to our fund size, the math seemed to work without significant reserves if we purchased enough ownership upfront and, as Founder Collective notes, it seems to align better with founders and our growth-stage co-investors.

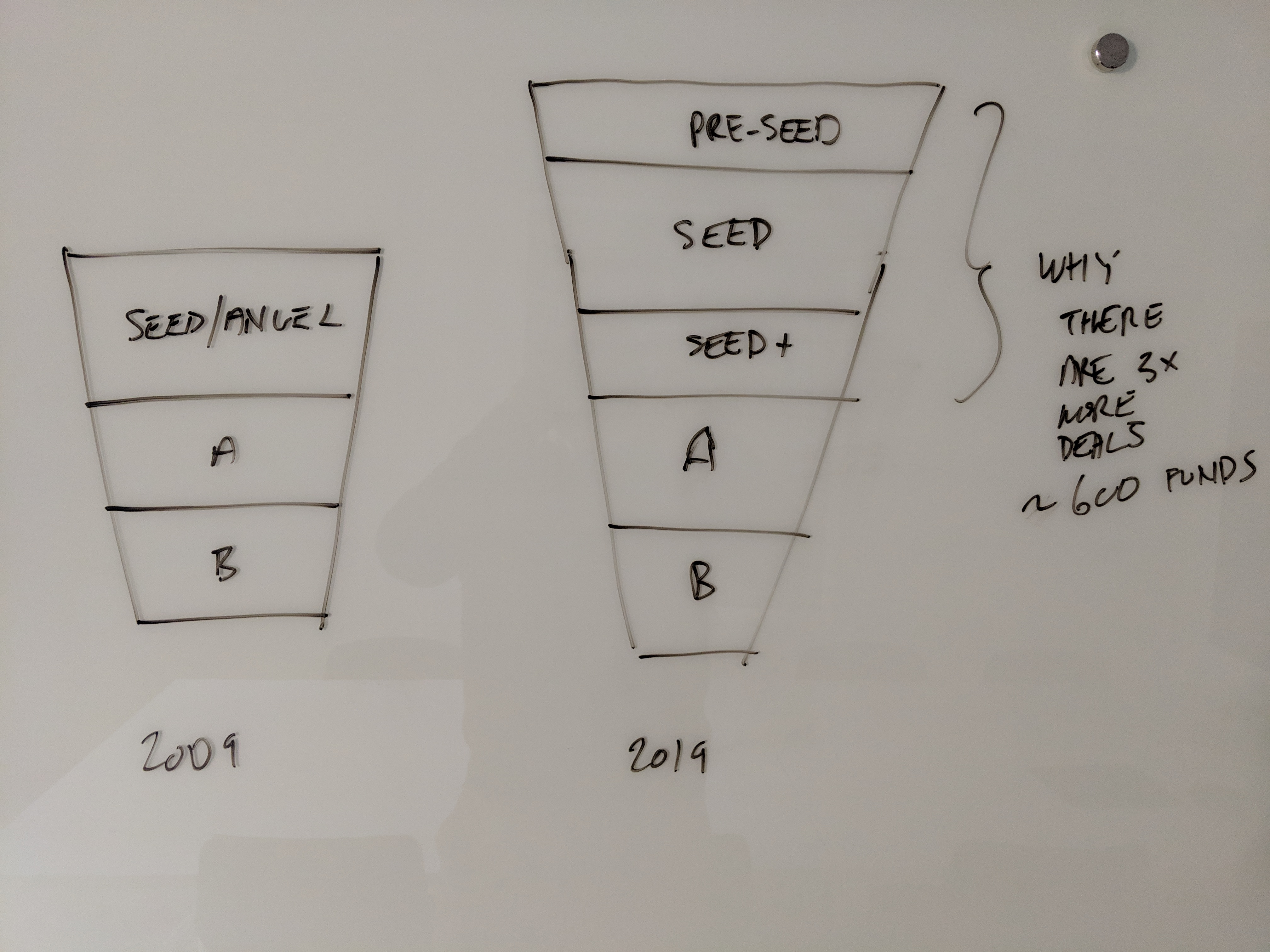

Longer funnel (not wider)

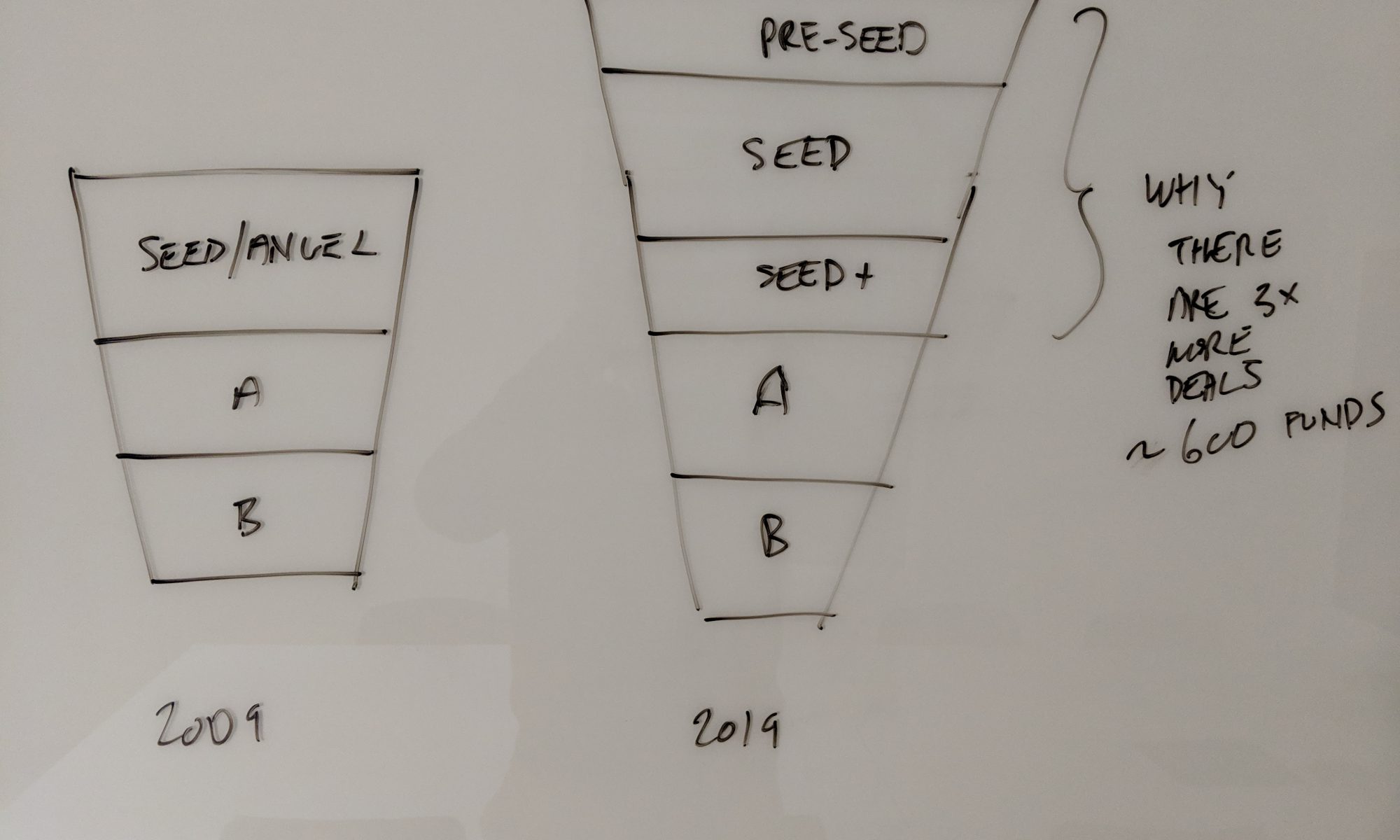

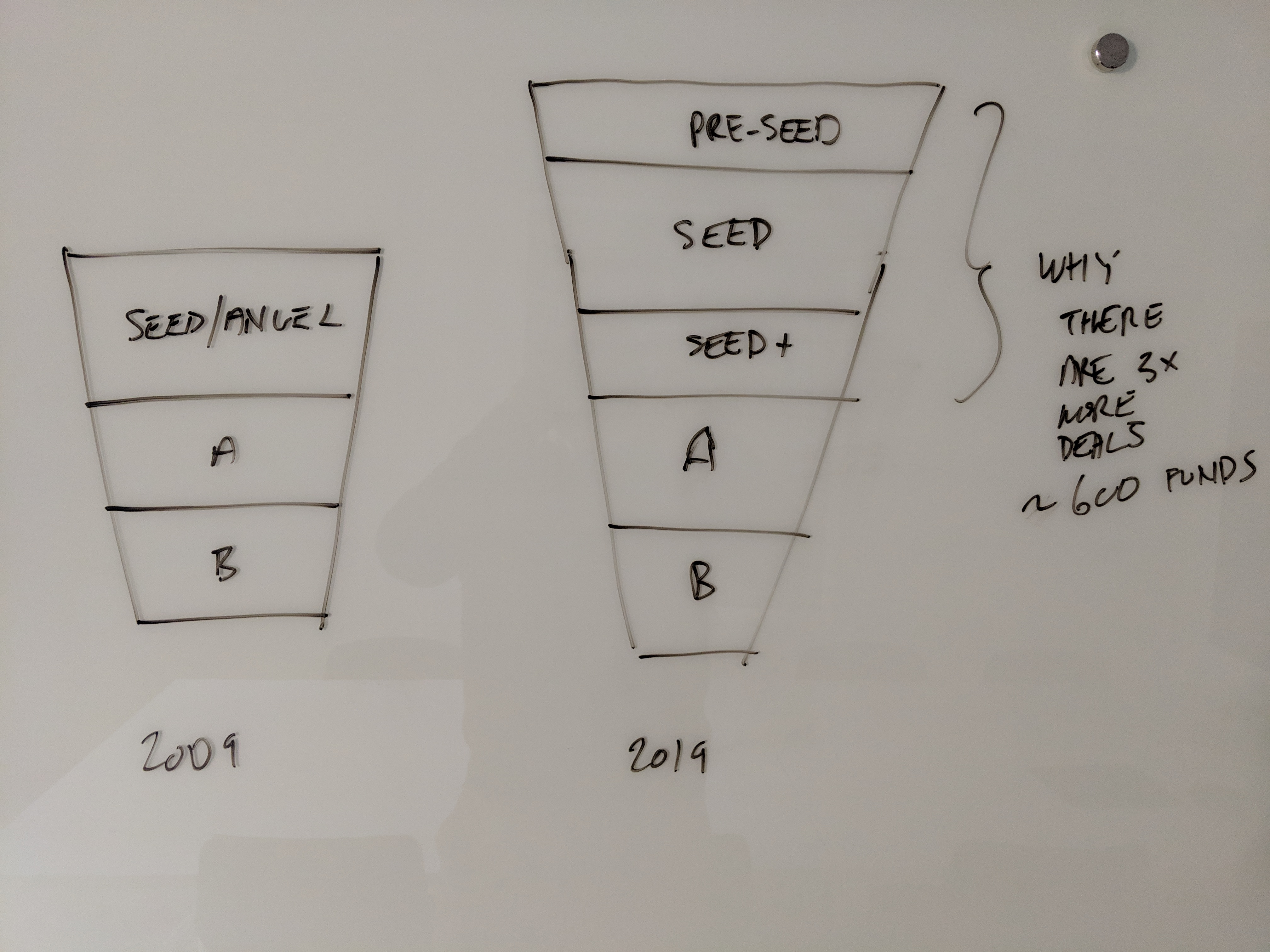

We’ve seen two major changes since we first started investing 12 years ago. The first is well-reflected by a recent deck shared by Mark Suster at Upfront, and highlighted in the slide shown below. It seems like the top of the funding funnel is getting wider.

It’s true that seed stage has grown 3x in the last decade. But that doesn’t necessarily mean the funnel only got wider. It also made it taller, like the image below.

One way to think about this — what used to be a sequence of “seed, A, B” is now, often, but not always a new sequence of “pre-seed, seed and seed+.”

Series A investments are totally different today than they were 10 years ago. But the Series A round is much more competitive because a lot of new money has shown up to play here and this makes accumulation and maintain models much harder, especially for seed and Series A stage-focused funds.

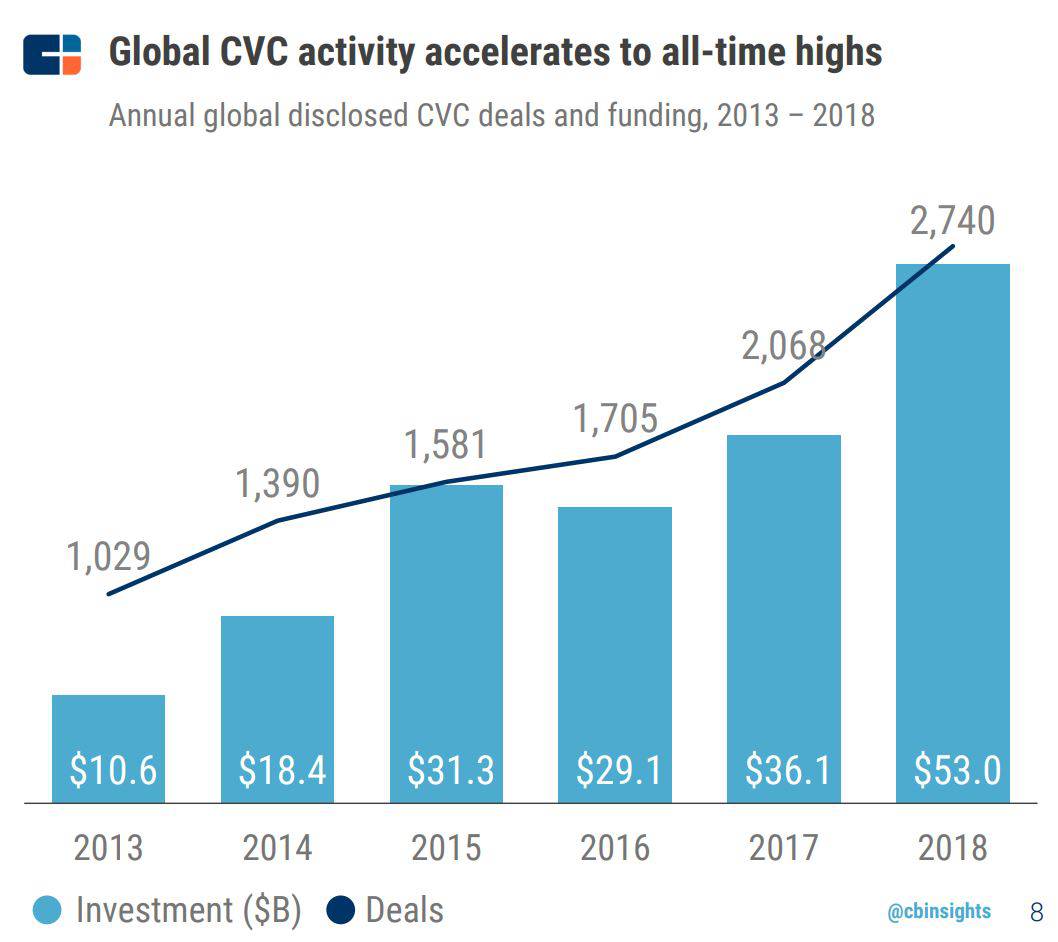

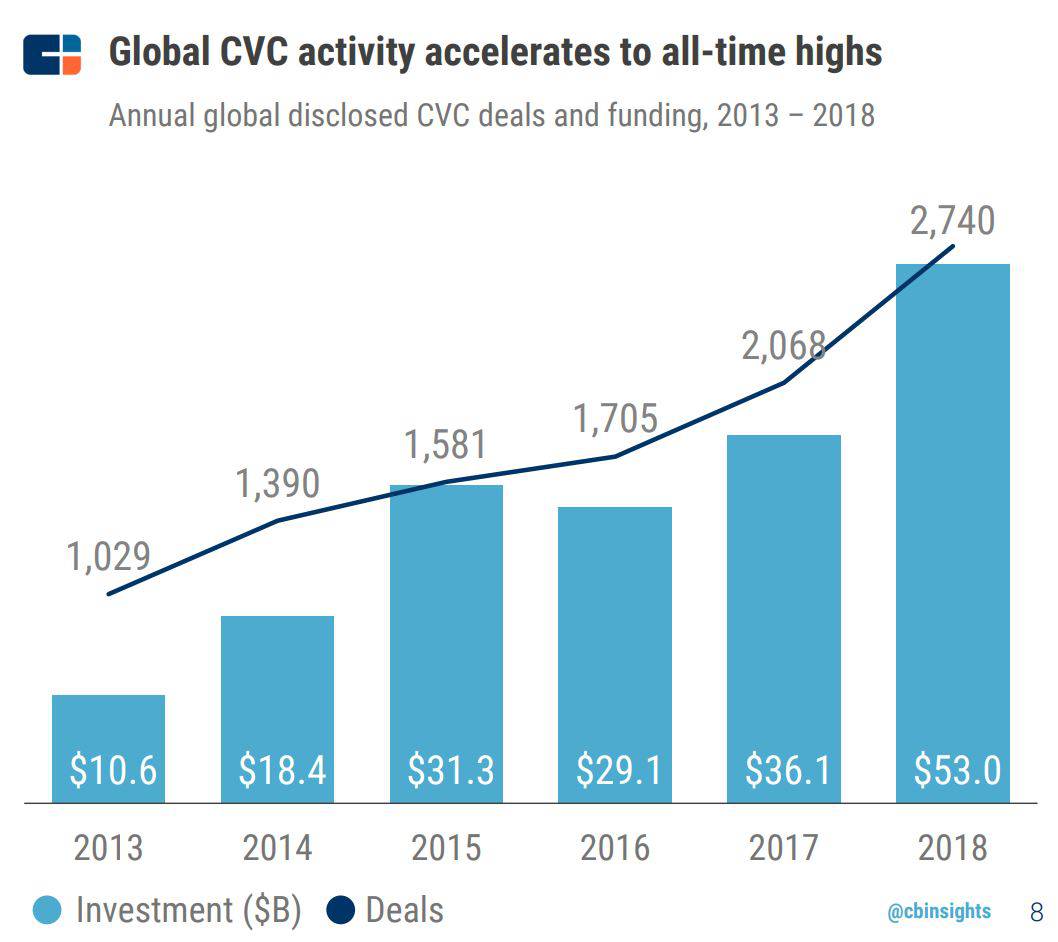

Who are these new players adding to the competition? Some are new VC funds, but a lot of them are corporate VC (CVC) funds.

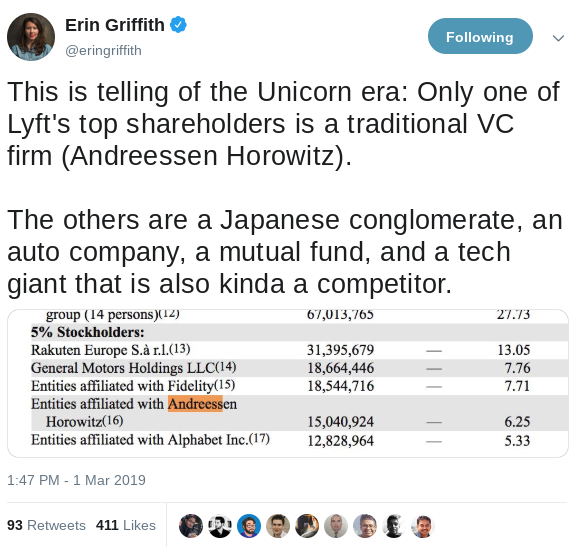

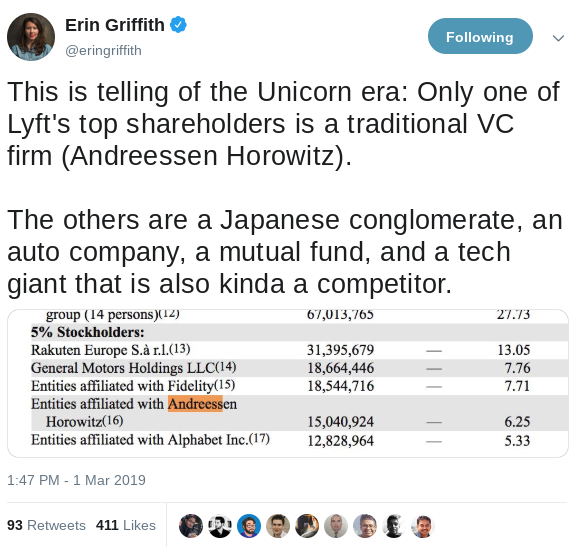

Where is all this CVC money going? We’re pretty sure it’s not in pre-seed or seed, though there is some CVC fund of fund activity into seed funds, but that’s not reflected in this data. And we’ve only seen a few instances of seed+ CVC activity. Interestingly, to find a good example of this, you probably don’t have to look further than Lyft’s S-1, where GM and Rakuten join better-known tech CVC Alphabet.

Regarding the founder conversation referenced earlier, the round is coming together because of a strategic investor who is leading it. This has become more common. Like Lyft’s team, founders understand tech and value sector-specific corporate investors as partners.

We don’t think we’ll see a slowdown in CVC interest any time soon because, much like their big tech counterparts, incumbents in sectors from transportation and real estate to energy and infrastructure all realize that the startup ecosystem is now an extension of their product development process — VC and M&A are now an extension of R&D.

It’s not just that there is more money competing for Series A or B deals now. That money has different goals beyond pure financial returns and the value add is different from VCs. CVCs often bring distribution, ecosystem and domain expertise. So the end result is more competitive A or B rounds and more complex pro-rata discussions.

Strategic pro-rata shuffle

Founders are still trying to sell no more than 20 percent of their company, while traditional VCs are trying to buy 20 percent and we still have to figure out pro-rata for existing investors while making room for growing interest from strategic investors.

For Urban Us, we’ve embraced these new round dynamics — they may make growth-stage allocations a bit more tricky, but strategic investors can deliver a lot of value. One clear result — it’s sometimes better for us not to take our pro-rata at series A.

High conviction before Series A

We tend to think of high conviction as a Series A idea — i.e. Series A investors who accumulate, maintain or use opportunity funds. But the same concept is now at work in the tall part of the funnel — the two or three stages before Series A.

We’ve long been fans of accelerator models like YC, Launch or Techstars. We’ve co-invested with all of them. While there was a sense that “not following” presented signaling risk, accelerators have found creative ways to sidestep the issue — for example, joining rounds only if there is another lead. So this means they can concentrate holdings before Series A.

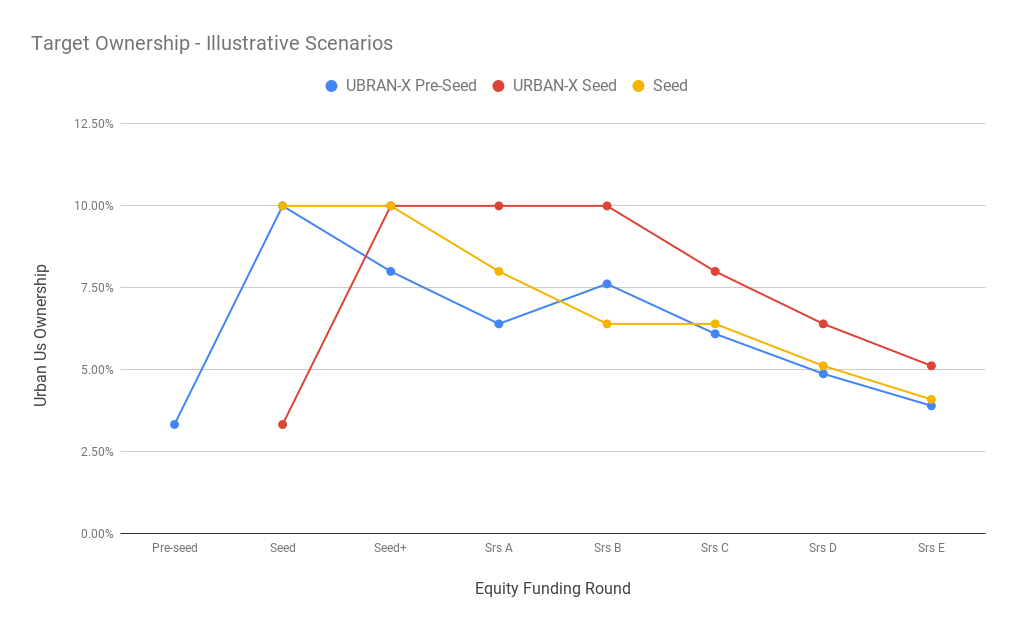

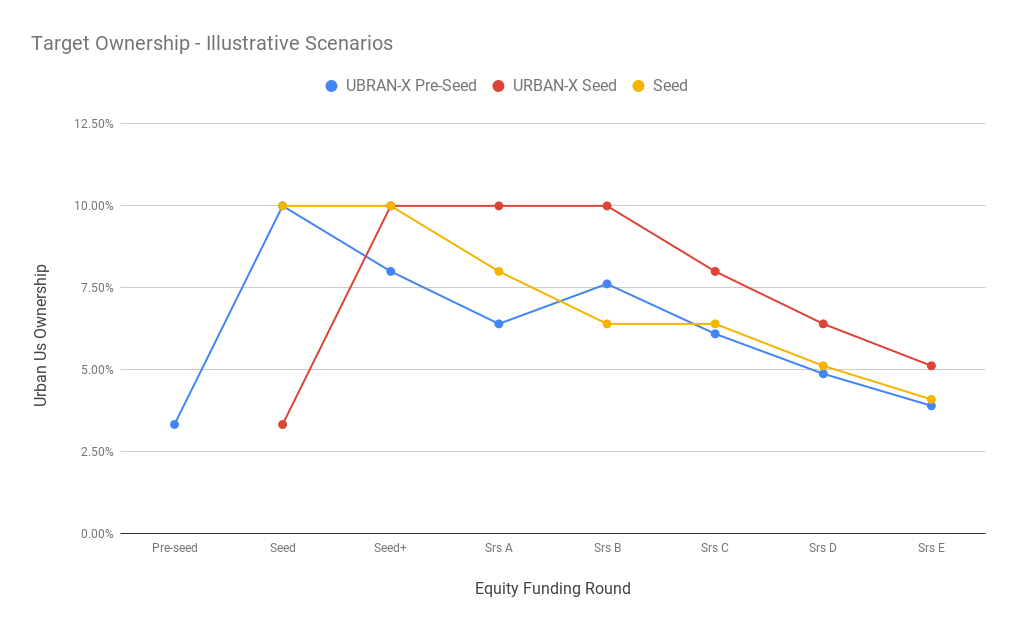

We now have our own accelerator, URBAN-X, because we’re best positioned to help address some unique challenges for the urbantech companies we’re looking to back. This allows us to be the first investor in most of our portfolio companies. And we can own enough of the company before Series A so we can still achieve our fully diluted ownership targets on behalf of our LPs.

As we look over scenarios related to when we first invest or when we think it will be hard to get pro-rata, we can find a few different paths to a target ownership position at exit. Some variations are shown below reflecting our approach for our newest fund.

The math

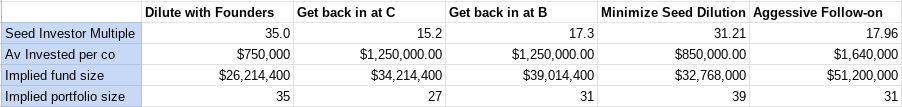

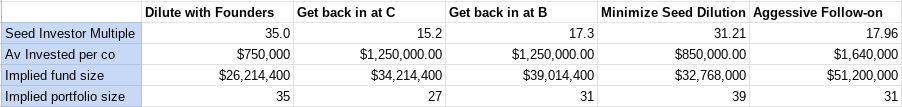

Obviously there are many different paths to ownership, especially in a world with two or three rounds happening before Series A. We’ve run a few simulations to understand the impact of different follow-on strategies. To explore different seed-stage allocation approaches, we modified Fred Wilson’s “Doubling Model” to explore a few of the variations. Only one change — we replaced Series A with seed+ as it’s more inline with what we’ve seen. It’s also important because it implies one less round of dilution in some seed strategies. We also assumed most seed investors invest in syndicates, so they don’t buy 20 percent unless they’re on the large end of fund sizes – i.e. $100 million+.

We explored what happens when seed investors make a single investment to buy 10 percent of a company and never follow-on and how might that compare to selective B and C-stage follow-ons or using progress from seed to seed rounds to avoid dilution on more promising companies. There is also the question of the implied fund size and number of investments — if you can make high conviction bets early, you get to make more investments even with a relatively small fund. But eventually you bump into time constraints for partners — getting to 40 deals with two partners can work, but presumes you are not a lone wolf partner and that you make hard choices about where to allocate time — which often seems harder than allocating money.

Up to about $50 million there are a range of possible strategies that can work, but diluting with founders allows more investments, even with smaller funds versus more traditional aggressive follow-on. More deals may be essential to the success of this model. Here’s our modified version of the doubling model (changes to the model are noted with blue cells).

Diluting alongside founders

VCs routinely remind founders that they shouldn’t worry about dilution because they will have a smaller share, but the pie will be bigger. Mostly this math works for founders, so why not VCs? Founder Collective is the only other firm we found that is explicit about aiming for this result. And this may be even more necessary today to make room for more strategic VCs to join traditional VCs.

At Urban Us our investment model is focused on getting fully diluted ownership before Series A. If we can do some pro-rata or sometimes if we need to do a bridge to buy teams more time, we’ll do that. And we’ll be equally excited when founders are able to bring in great new investors to help them through their next growth stage, regardless of their allocation strategy.

Source: Tech Crunch