Nik Milanovic

Contributor

Nik Milanovic is a fintech and financial inclusion enthusiast, with a decade of work across mobile payments, online lending, credit and microfinance.

More posts by this contributor

With the release of the Facebook consortium’s project Libra whitepaper, the internet, tech world, financial services industry and policy circles are all burning with conversation on the project’s potential. We are still very early into Libra’s life — it is, after all, still a proposal — and there is an endless set of questions left to answer. The project could redefine how we view money or it could be a complete failure; we won’t know which for years to come.

While there isn’t much to add to the (likely thousands) of pundit takes on the project until more details come out, this moment does provide us with an opportunity to step back and take a look at money itself. We should be asking ourselves: how does money work today and how should it work?

Money is an anachronistically analog part of everyday life. The last 25 years saw the digitization of most services businesses, from communications (email) to bookstores (Amazon) to taxis (Uber). Yet, even with the rise of fintech and significant innovation in consumer finance, money itself has remained curiously unchanged.

The future of money is just beginning.

There are good reasons for money to have remained unchanged. Currencies are controlled and issued by states, and for many reasons, they need to be controlled and issued by states. But the reasons are a reflection of the “facts on the ground” today. Money is too sensitive and too critical to allow for the same level of disruptive innovation we’ve seen in other assets. But if we were to design money de novo today from a Rawlsian original position, it would probably look pretty different.

Libra gives us an opportunity to talk more openly not just about what money is, but about what money should be. And regardless of what happens with Libra — which faces regulatory and competitive headwinds — the moment won’t be wasted if we take this time to contemplate the future of money. Below are some (not collectively exhaustive) starting ideas for that conversation, from the most basic to the more exotic.

Money should be free

Let’s start with the most obvious: put simply, it shouldn’t cost anyone money to use money. Financial institutions and fintechs are (slowly) moving toward this consensus, but in many cases, people still have to pay just to access their money.

ATMs charge fees for withdrawals. Checks cost money to print (and for those who feel the U.S. is moving past them, 90% of checks are still written in the U.S.). Foreign remittances incur transfer fees, bank-to-bank wires incur fees, check-cashing incurs fees, paying vendors with PayPal incurs fees, etc. etc.

The early promise of apps like Venmo, Square Cash and WeChat Pay (and earlier, Clinkle) is to let people transfer and use their money at no cost. Apple Pay and Google Pay take that promise a step further by making the phone — not the dollar — the primary instrument for in-person purchases — all at no cost to debit directly from a bank or credit card account.

But these apps have no equivalent in many countries. While mobile money services like M-Pesa have been ubiquitously successful in Kenya and neighboring countries, countries like Nigeria — Africa’s largest economy — still have significant cost of cash problems and expensive policy restrictions on the use of cash. I ran into many “Unable to dispense cash” error messages in my time in east Africa, where just having a bank account could incur non-trivial costs.

Incurring a fee just to use money is an outdated standard.

Money should transfer instantly

To most people reading this, the difference between instant payments and those that take a couple of days is not significant. A paycheck could come on Friday or Monday. A Venmo cashout can take a day or two to hit a bank account.

But as Aaron Klein at Brookings notes, slow payments disproportionately affect poor people. The time it takes for a check to clear, for remittance funds to settle or for payroll to be deposited can mean the difference between paying a bill and incurring an overdraft fee. It can mean not having enough money for weekend grocery shopping. These realities drive consumers to turn to payday lenders ($7 billion in annual fees), check cashers ($2 billion) or overdraft fees ($24 billion!).

Identity should be programmed into money.

As NPR noted when they waited for a Kickstarter payment, “We just need Amazon’s bank to send money electronically to a checking account at Chase bank. It’s just information traveling over wires. How long could it take: A minute? An hour? It took five days.” That is because the rails on which money is moved in the U.S. are more than 40 years old. As Klein notes, you can now send money more quickly from Slovakia to France than DC to Philly — and fixing this delay could be the single fastest way to combat wealth inequality in the United States.

This is another obvious easy win for the future of money.

And signs of that future are emerging. Apps like Earnin and employers like Walmart are paying workers in real time, to allow people to use their money as soon as they earn it. Libra’s own website opines that getting and using money “should be as easy and cheap as sending a text message.” Money should move at the speed of communications.

Money should take ‘one click’ to use

Amazon is notorious for pursuing one-click purchase technology, removing the last small obstacles between consumers and their buying decisions. Money should be no different: moving money to savings, sending it to a friend, making a loan or investment, paying a bill — these activities could all use a more frictionless UI upgrade. Unfortunately, today, accessing your money frequently requires a string of passwords, PINs, IDs or 2FA — all absolutely critical for security, but friction-inducing.

Fortunately, digital identity systems have been a ripe area for innovation in the past few years. Smartphone OS’s now allow people to use biometric identifiers — like fingerprints or Face ID — to authorize the use of their money, with mixed success. Decentralized identity systems like 3Box sell the promise of one universal, self-owned ID profile that can be used to permission any service built on top of it (including financial ones).

Identity should be programmed into money. If units of currency can have an “ownership” field, that field can be unlocked using more frictionless identifiers tied to the user and then re-coded when ownership is changed, making one-click use possible. (This could operate similarly to Everledger’s diamond registration program.) This could also prevent theft: If the “ownership” identity field is secure enough only to be altered in legitimate transfers, money could also be programmed to be unusable if that field is transferred improperly (i.e. stolen). This brings up a related point…

Money should be secure

One of the cities with the fastest rate of mobile payments adoption is Mogadishu, Somalia. Why? Because mobile money is safe — in Mogadishu, where muggings are frequently deadly, carrying cash can be a matter of life or death. The future of money is one in which physical theft is no longer possible because money is securely digitized.

Money should be stable

While theft drives mobile money adoption in Somalia, a BBC report titled The surprising place where cash is going extinct found a different driver of cashless payments in neighboring Somaliland: hyperinflation. The rapidly devaluing Somaliland shilling has made goods that were previously affordable two times as expensive in as many years, leading shoppers to opt for mobile dollars over bundles of cash.

This is one of the expressed promises of Libra and other stablecoins like the Gemini Dollar or the ill-fated Basis: no wild fluctuations. As Caitlin Long points out, “central banks in developing countries are notorious for their lack of discipline in maintaining the value of their fiat currencies, which too often lose purchasing power.” A global, consortium-moderated currency could tame that irresponsibility.

How does money work today and how should it work?

Hyperinflation isn’t as rare as it sounds. It was the status quo two years ago when I visited Zimbabwe and goods were quoted in three prices. Over the last year in Europe, Turkey’s lira dropped 25% in value in its own crisis. And today in Venezuela, inflation stands at over 1,000,000%, making goods un-buyable. The most common explanation for these events is that they happen when people lose faith in governments to protect the value of their currency. The drop in value led to massive capital flight, ironically, to Bitcoin as a source of stability (including a Bitcoin ATM in Harare, Zimbabwe’s capital).

Interestingly, the Libra is not the first supranational currency to be proposed (see economist John Maynard Keynes’ Bancor plan). It isn’t even the first international reserve currency based on a basket: the IMF maintains the XDR, a currency pegged to a weighted mix of dollars, euros, yuan, yen and pounds (the Libra will be fiat-pegged to all those, less the yuan). But the Libra would be the first non-sovereign global reserve currency competitor, and the first one that individual people could actually use.

It remains to be seen whether the Libra itself one day gains enough intrinsic value (what Matt Levine refers to as a collective fiction) to separate from its underlying basket of currencies, the same way the U.S. dollar left the gold standard.

The money of the future should not be intrinsically tied to faith in local government — it should retain its value and stability independently so that it doesn’t risk rapid devaluation.

Money should be interoperable

The internet could have developed very differently. If we look back to the early days of the internet, there was always a chance that multiple competitive “walled garden” internets grew side by side, competing for users, and refusing to talk with each other. Fortunately, thanks to the work of nonprofit governing bodies like ICANN, the world mostly runs on one internet. Even in countries like China that wall off certain websites, internet pages still talk to each other using the same set of protocols that they do everywhere else in the world.

Money should be no different. It should be as easy to buy lunch with a currency in one country as with that same currency in another. The same payment protocol should underlie any type of purchase, physical or digital. Transferring between currencies should be instantaneous and free, not require visiting an (online or digital) exchange.

The explosion in cryptocurrencies built around narrowly vertical use-cases has been interesting to watch, but true adoption will only come with a universal resolver that allows people to frictionlessly move between use-cases without manually switching their unit of currency.

Different types of money should be use-based, not geography-based

Branching out from the prior point: What if money had built-in rules that determined what it was useful for? Dan Jeffries provides some instructive examples of what this could look like: deflationary coins could automatically adjust their value to track inflation. Inflationary tokens could be built to lose value quickly to incentivize spending.

Governments could reward spending on environmentally friendly goods by creating currencies that automatically discounted the prices of those goods. Currencies could have rewards and loyalty programs (e.g. Starbucks) automatically built in. Currencies could expire if not used in a given window, or only activate upon a certain date or trigger action. This is the promise of cryptocurrencies as “programmable money” rather than just “digital gold” (the Ethereum/Bitcoin debate).

Money should be an open development platform

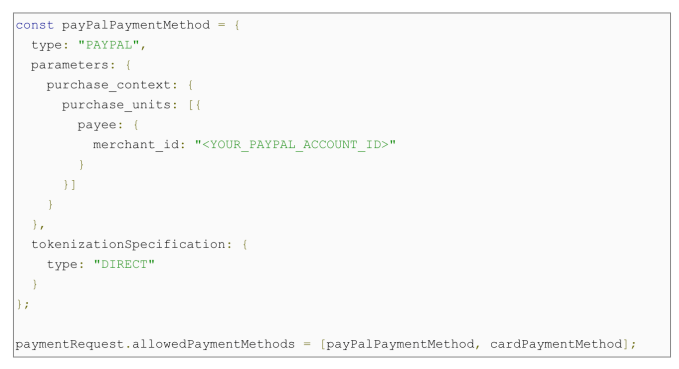

If money becomes programmable, the possibilities for what can be built on top of money are endless and unexplored. Some of the most obvious examples are financial applications (like Calibra, the project Libra wallet).

It shouldn’t cost anyone money to use money.

The existence and ubiquity of a single-digital currency is just the first step. Following that step are applications, like lending (institutional or peer-to-peer), investing, savings, gift-giving, etc. Imagine, as a use case, being able to ping your bank via text and ask for a one-week microloan to cover a big purchase — and the loan being approved and sent back to you by text. Or imagine your kids’ allowance automatically accruing to them weekly via text — and an allowance “bonus” applied to any money they set aside for savings instead of spending. As David Graeber would note, it’s these credit and investment applications that create the potential for true growth in a financial ecosystem.

Many view Libra as a future platform, like the iOS Apple Store, that will house a potentially infinite volume of applications built on top of it. These could be universal rideshare apps, airline rewards accounts, e-commerce experiences, etc. that all plug into the same rails that your money is built on, so that the UI is entirely driven by the user intent (e.g. buying something) without requiring you to move any money between accounts.

Money should have (some) guardrails

The last feature money should have is built-in guardrails. This is the most controversial claim here, and one that will ruffle the feathers of the censorship-resistant, self-sovereign crypto community.

Digital money has the potential of traceability and programmable rules to create safety guardrails and prevent, for example, terrorist financing, black-market purchases, money laundering, transfer of stolen funds, etc. Libra, with its strict know-your-customer standards, will certainly work with financial regulators to ensure that it is meeting these guardrail standards. (Even though early reactions from legislators have run the gamut from skeptical to apoplectic.)

Yet there are sound reasons to be skeptical of digital money guardrails. Repressive regimes could use them to contain capital flight and offshoring (a key use case for Bitcoin in China). They could target an individual’s wallet to shut down their freedom of movement or purchase, and precisely trace their physical location. Back-door hacks that abuse guardrail functionality to disable money could have the effect of entirely freezing a country’s infrastructure and bringing down its financial system. It’s important to counterweight these possibilities when considering where guardrails should be set — and whether they should differ across borders.

The future of money is just beginning.

These are exciting times. The potential to move beyond centuries of slow progression in financial services has never been greater. The internet, combined with the ingenuity of blockchain and cryptosystems, could build the framework for a global network that brings the world onto one universal monetary standard. There are many questions to answer between here and there, but with Libra acting as a catalyst, people are finally beginning to ask them. Get ready for more innovation to come — this is just the beginning.

Source: Tech Crunch