The underpinnings of how app store analytics platforms operate were exposed this week by BuzzFeed, which uncovered the network of mobile apps used by a popular analytics firm Sensor Tower to amass app data. The company had operated at least 20 apps, including VPNs and ad blockers, whose main purpose was to collect app usage data from end users in order to make estimations about app trends and revenues. Unfortunately, these sorts of data collection apps are not new — nor unique to Sensor Tower’s operation.

Sensor Tower was found to operate apps such as Luna VPN, for example, as well as Free and Unlimited VPN, Mobile Data, and Adblock Focus, among others. After BuzzFeed reached out, Apple removed Adblock Focus and Google removed Mobile Data. Others are still being investigated, the report said.

Apps’ collection of usage data has been an ongoing issue across the app stores.

Facebook and Google have both operated such apps, not always transparently, and Sensor Tower’s key rival App Annie continues to do the same today.

Facebook

For Facebook, its 2013 acquisition of VPN app maker Onavo for years served as a competitive advantage. The traffic through the app gave Facebook insight into what other social applications were growing in popularity — so Facebook could either clone their features or acquire them outright. When Apple finally booted Onavo from the App Store half a decade later, Facebook simply brought back the same code in a new wrapper — then called the Facebook Research app. This time, it was a bit more transparent about its data collection, as the Research app was actually paying for the data.

But Apple kicked that app out, too. So Facebook last year launched Study and Viewpoints to further its market research and data collection efforts. These apps are still live today.

Google

Google was also caught doing something similar by way of its Screenwise Meter app, which invited users 18 and up (or 13 if part of a family group) to download the app and participate in the panel. The app’s users allowed Google to collect their app and web usage in exchange for gift cards. But like Facebook, Google’s app used Apple’s Enterprise Certificate program to work — a violation of Apple policy that saw the app removed, again following media coverage. Screenwise Meter returned to the App Store last year and continues to track app usage, among other things, with panelists’ consent.

App Annie

App Annie, a firm that directly competes with Sensor Tower, has acquired mobile data companies and now operates its own set of apps to track app usage under those brands.

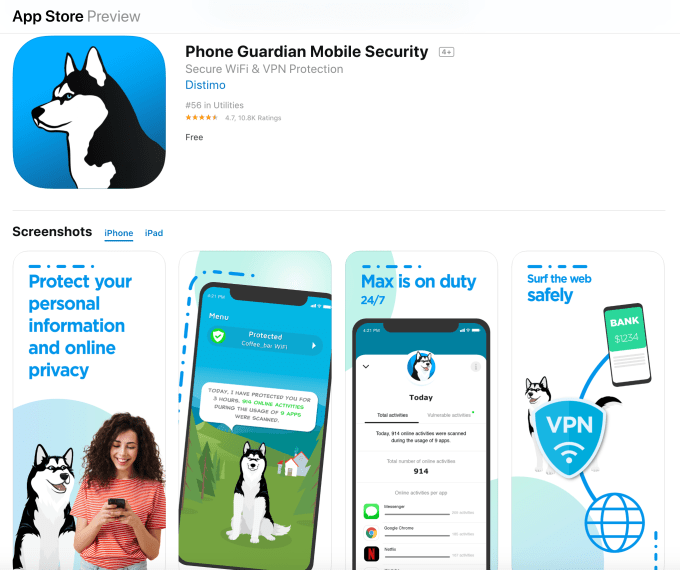

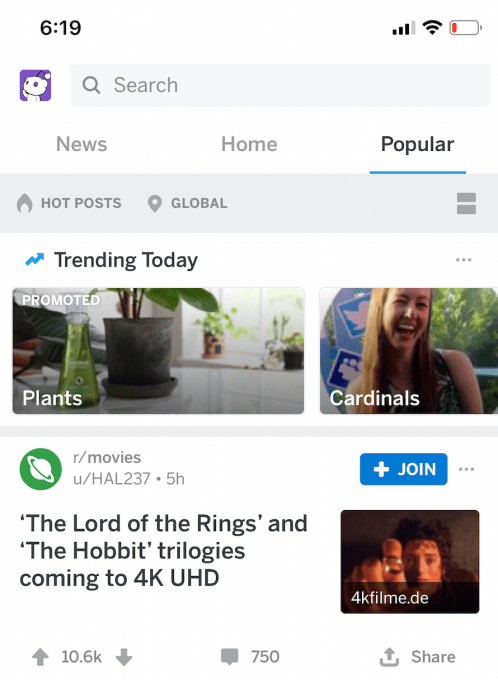

In 2014, App Annie bought Distimo, and as of 2016 has run Phone Guardian, a “secure Wi-Fi and VPN” app, under the Distimo brand.

The app discloses its relationship with App Annie in its App Store description, but remains vague about its true purpose:

“Trusted by more than 1 million users, App Annie is the leading global provider of mobile performance estimates. In short, we help app developers build better apps. We build our mobile performance estimates by learning how people use their devices. We do this with the help of this app.”

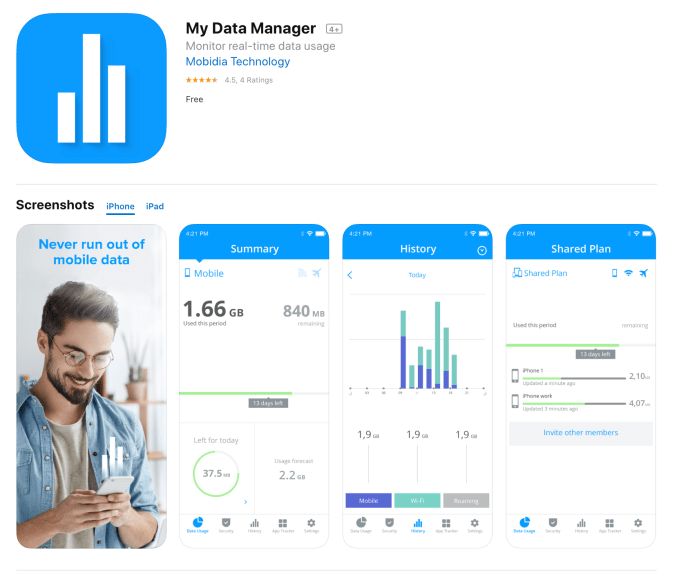

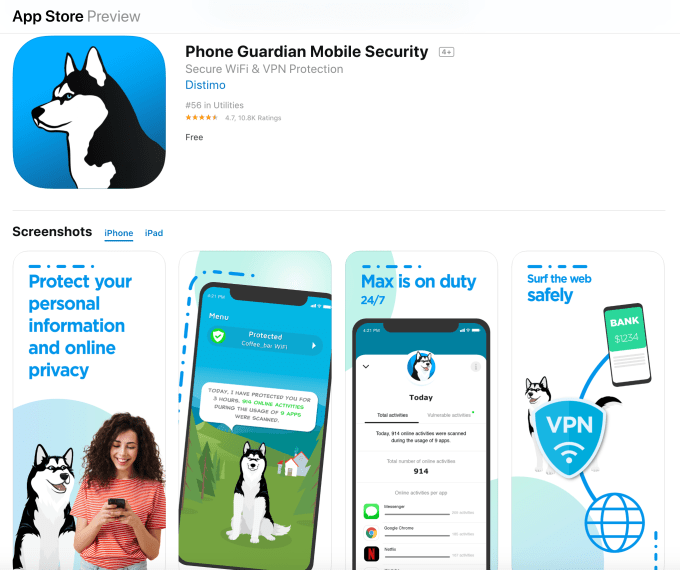

In 2015, App Annie acquired Mobidia. Since 2017, it has operated a real-time data usage monitor My Data Manager under that brand, as well. The App Store description only offers the same vague disclosure, which means users aren’t likely aware of what they’re agreeing to.

Disclosure?

The problem with apps like App Annie’s and Sensor Tower’s is that they’re marketed as offering a particular function, when their real purpose for existing is entirely another.

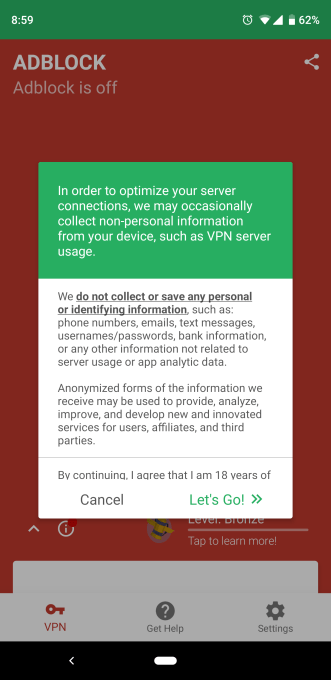

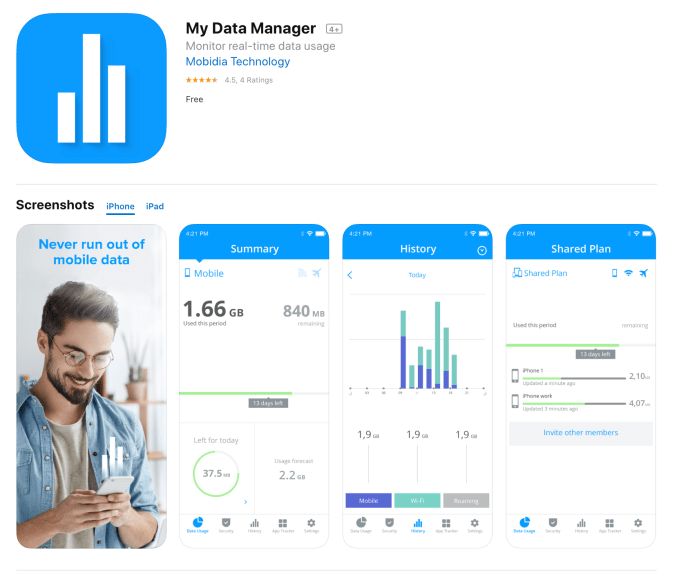

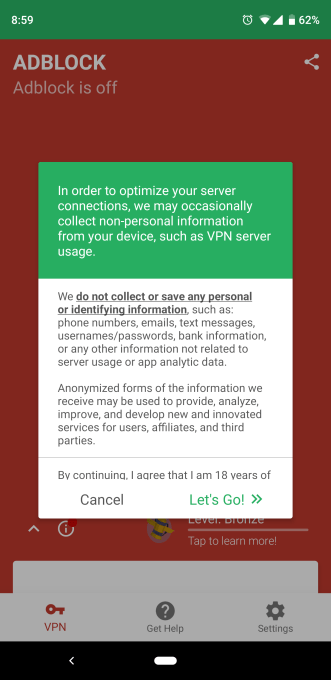

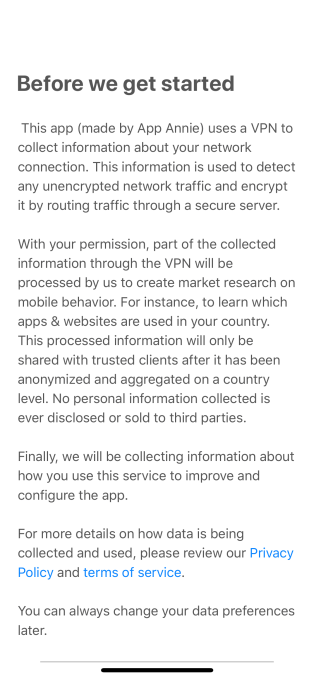

The app companies’ defense is that they do disclose and require consent during onboarding. For example, Sensor Tower apps explicitly tell users what is collected and what is not:

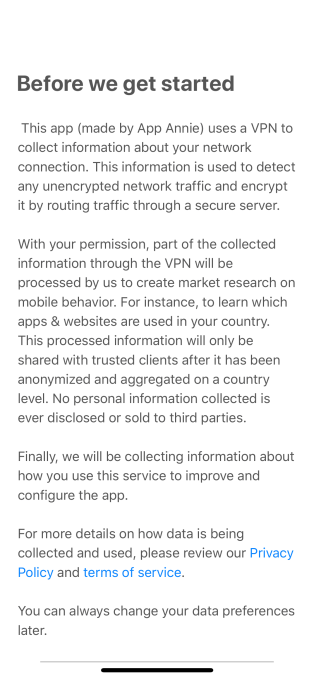

App Annie’s app offers a similar disclosure, and takes the extra step of identifying the parent company by name:

App Annie also says its apps can continue to be used even if data-sharing is turned off.

Despite these opt-ins, end users may still not understand that their VPN app is actually tied to a much larger data collection operation. After all, App Annie and Sensor Tower aren’t household names (unless you’re an app publisher or marketer.)

Apple and Google’s responsibility

Apple and Google, let’s be fair, are also culpable here.

Of course, Google is more pro-data collection because of the nature of its own business as an advertising-powered company. (It even tracks users in the real-world via the Google Maps app.)

Apple, meanwhile, markets itself as a privacy-focused company, so is deserving of increased scrutiny.

It seems unfathomable that, following the Onavo scandal, Apple wouldn’t have taken a closer look into the VPN app category to ensure its apps were compliant with its rules and transparent about the nature of their businesses. In particular, it seems Apple would have paid close attention to apps operated by companies in the app store intelligence business, like App Annie and its subsidiaries.

Apple is surely aware of how these companies acquire data — it’s common industry knowledge. Plus, App Annie’s acquisitions were publicly disclosed.

But Apple is conflicted. It wants to protect app usage and user data (and be known for protecting such data) by not providing any broader app store metrics of its own. However, it also knows that app publishers need such data to operate competitively on the App Store. So instead of being proactive about sweeping the App Store for data collection utilities, it remains reactive by pulling select apps when the media puts them on blast, as BuzzFeed’s report has since done. That allows Apple to maintain a veil of innocence.

But pulling user data directly covertly is only one way to operate. As Facebook and Google have since realized, it’s easier to run these sorts of operations on the App Store if the apps just say, basically, “this is a data collection app,” and/or offer payment for participation — as do many marketing research panels. This is a more transparent relationship from a consumer’s perspective too, as they know they’re agreeing to sell their data.

Meanwhile, Sensor Tower and App Annie competitor Apptopia says it tested then scrapped its own an ad blocker app around six years ago, but claims it never collected data with it. It now favors getting its data directly from its app developer customers.

“We can confidently state that 100% of the proprietary data we collect is from shared App Analytics Accounts where app developers proactively and explicitly share their data with us, and give us the right to use it for modeling,” stated Apptopia Co-founder and COO, Jonathan Kay. “We do not collect any data from mobile panels, third-party apps, or even at the user/device level.”

This system (which is used by the others as well) isn’t necessarily better for end users, as it further obscures the data collection and sharing process. Consumers don’t know which app developers are sharing this data, what data is being shared, or how it’s being utilized. (Fortunately for those who do care, Apple allows users to disable the sharing of diagnostic and usage data from within iOS Settings.)

Data collection done by app analytics firms is only one of many, many ways that apps leak data, however.

In fact, many apps collect personal data — including data that’s far more sensitive than anonymized app usage trends — by way of their included SDKs (software development kits). These tools allow apps to share data with numerous technology companies including ad networks, data brokers, and aggregators, both large and small. It’s not illegal and mainstream users probably don’t know about this either.

Instead, user awareness seems to crop up through conspiracy theories, like “Facebook is listening through the microphone,” without realizing that Facebook collects so much data it doesn’t really need to do so. (Well, except when it does).

In the wake of BuzzFeed’s reporting, Sensor Tower says it’s “taking immediate steps to make Sensor Tower’s connection to our apps perfectly clear, and adding even more visibility around the data their users share with us.”

Apple, Google, and App Annie have been asked for comment. Google isn’t providing an official comment. Apple didn’t respond.

Sensor Tower’s full statement is below:

Our business model is predicated on high-level, macro app trends. As such, we do not collect or store any personally identifiable information (PII) about users on our servers or elsewhere. In fact, based on the way our apps are designed, such data is separated before we could possibly view or interact with it, and all we see are ad creatives being served to users. What we do store is extremely high level, aggregated advertising data that may demonstrate trends that we share with customers.

Our privacy policy follows best practices and makes our data use clear. We want to reiterate that our apps do not collect any PII, and therefore it cannot be shared with any other entity, Sensor Tower or otherwise. We’ve made this very clear in our privacy policy, which users actively opt into during the apps’ onboarding processes after being shown an unambiguous disclaimer detailing what data is shared with us. As a routine matter, and as our business evolves, we’ll always take a privacy-centric approach to new features to help ensure that any PII remains uncollected and is fully safeguarded.

Based on the feedback we’ve received, we’re taking immediate steps to make Sensor Tower’s connection to our apps perfectly clear, and adding even more visibility around the data their users share with us.

App Annie shared the following:

App Annie does not use root certificates at any point in its data collection process.

App Annie discloses that when users opt into data collection (and data sharing is not mandatory to use our apps), data will be shared with App Annie for the purposes of creating market research. We only collect data after users expressly consent to this collection within our apps. We are very transparent, both on the app stores and in the apps themselves and clearly connect App Annie to our mobile apps.

Source: Tech Crunch