Professor Michael Huth (Ph.D.) is co-founder and CTO of

Xayn and teaches at Imperial College London. His research focuses on cybersecurity, cryptography and mathematical modeling, as well as security and privacy in machine learning.

In the last decade we’ve seen massive changes in how we consume and interact with our world. The Yellow Pages is a concept that has to be meticulously explained with an impertinent scoff at our own age. We live within our smartphones, within our apps.

While we thrive with the information of the world at our fingertips, we casually throw away any semblance of privacy in exchange for the convenience of this world.

This line we straddle has been drawn with recklessness and calculation by big tech companies over the years as we’ve come to terms with what app manufacturers, large technology companies, and app stores demand of us.

Our private data into the cloud

According to Symantec, 89% of our Android apps and 39% of our iOS apps require access to private information. This risky use sends our data to cloud servers, to both amplify the performance of the application (think about the data needed for fitness apps) and store data for advertising demographics.

While large data companies would argue that data is not held for long, or not used in a nefarious manner, when we use the apps on our phones, we create an undeniable data trail. Companies generally keep data on the move, and servers around the world are constantly keeping data flowing, further away from its source.

Once we accept the terms and conditions we rarely read, our private data is no longer such. It is in the cloud, a term which has eluded concrete understanding throughout the years.

A distinction between cloud-based apps and cloud computing must be addressed. Cloud computing at an enterprise level, while argued against ad nauseam over the years, is generally considered to be a secure and cost-effective option for many businesses.

Even back in 2010, Microsoft said 70% of its team was working on things that were cloud-based or cloud-inspired, and the company projected that number would rise to 90% within a year. That was before we started relying on the cloud to store our most personal, private data.

Cloudy with a chance of confusion

To add complexity to this issue, there are literally apps to protect your privacy from other apps on your smart phone. Tearing more meat off the privacy bone, these apps themselves require a level of access that would generally raise eyebrows if it were any other category of app.

Consider the scenario where you use a key to encrypt data, but then you need to encrypt that key to make it safe. Ultimately, you end up with the most important keys not being encrypted. There is no win-win here. There is only finding a middle ground of contentment in which your apps find as much purchase in your private data as your doctor finds in your medical history.

The cloud is not tangible, nor is it something we as givers of the data can access. Each company has its own cloud servers, each one collecting similar data. But we have to consider why we give up this data. What are we getting in return? We are given access to applications that perhaps make our lives easier or better, but essentially are a service. It’s this service end of the transaction that must be altered.

App developers have to find a method of service delivery that does not require storage of personal data. There are two sides to this. The first is creating algorithms that can function on a local basis, rather than centralized and mixed with other data sets. The second is a shift in the general attitude of the industry, one in which free services are provided for the cost of your personal data (which ultimately is used to foster marketing opportunities).

Of course, asking this of any big data company that thrives on its data collection and marketing process is untenable. So the change has to come from new companies, willing to risk offering cloud privacy while still providing a service worth paying for. Because it wouldn’t be free. It cannot be free, as free is what got us into this situation in the first place.

Clearing the clouds of future privacy

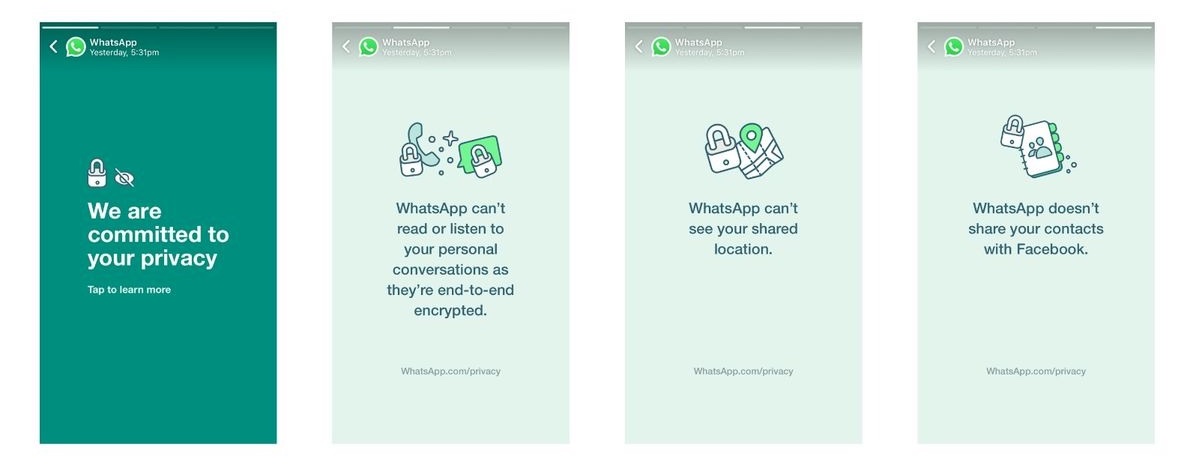

What we can do right now is at least take a stance of personal vigilance. While there is some personal data that we cannot stem the flow of onto cloud servers around the world, we can at least limit the use of frivolous apps that collect too much data. For instance, games should never need access to our contacts, to our camera and so on. Everything within our phone is connected, it’s why Facebook seems to know everything about us, down to what’s in our bank account.

This sharing takes place on our phone and at the cloud level, and is something we need to consider when accepting the terms on a new app. When we sign into apps with our social accounts, we are just assisting the further collection of our data.

The cloud isn’t some omnipotent enemy here, but it is the excuse and tool that allows the mass collection of our personal data.

The future is likely one in which devices and apps finally become self-sufficient and localized, enabling users to maintain control of their data. The way we access apps and data in the cloud will change as well, as we’ll demand a functional process that forces a methodology change in service provisions. The cloud will be relegated to public data storage, leaving our private data on our devices where it belongs. We have to collectively push for this change, lest we lose whatever semblance of privacy in our data we have left.

Source: Tech Crunch