Many corporations are pinning their futures on their venture investment portfolios. If you can’t beat startups at the innovation game, go into business with them as financial partners.

Though many technology companies have robust venture investment initiatives—Alphabet’s venture funding universe and Intel Capital’s prolific approach to startup investment come to mind—other corporations are just now doubling down on venture investments.

Over the past several months, several big corporations committed additional capital to corporate investments. For example, defense firm Lockheed Martin added an additional $200 million to its in-house venture group back in June. Duck-represented insurance firm Aflac just bumped its corporate venture fund from $100 million to $250 million, and Cigna lust launched a $250 million fund of its own. This is to say nothing of financial vehicles like SoftBank’s truly enormous Vision Fund, into which the Japanese telecom giant invested $28 billion of its own capital.

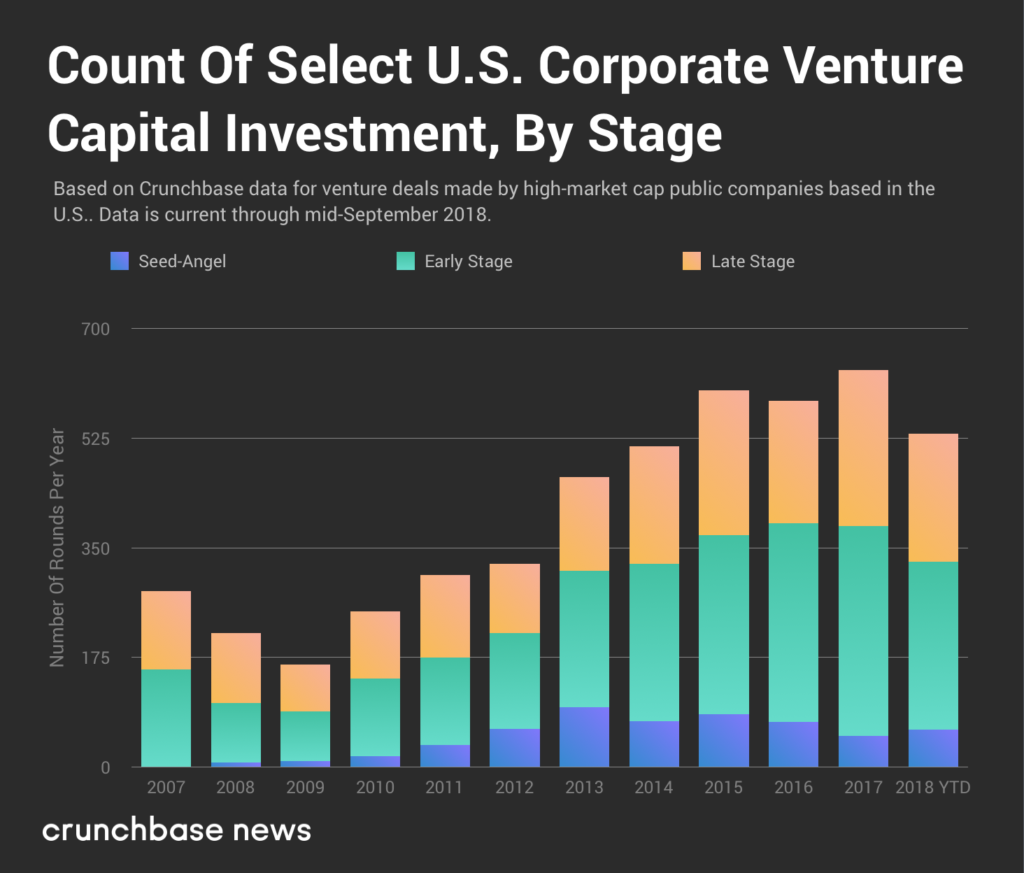

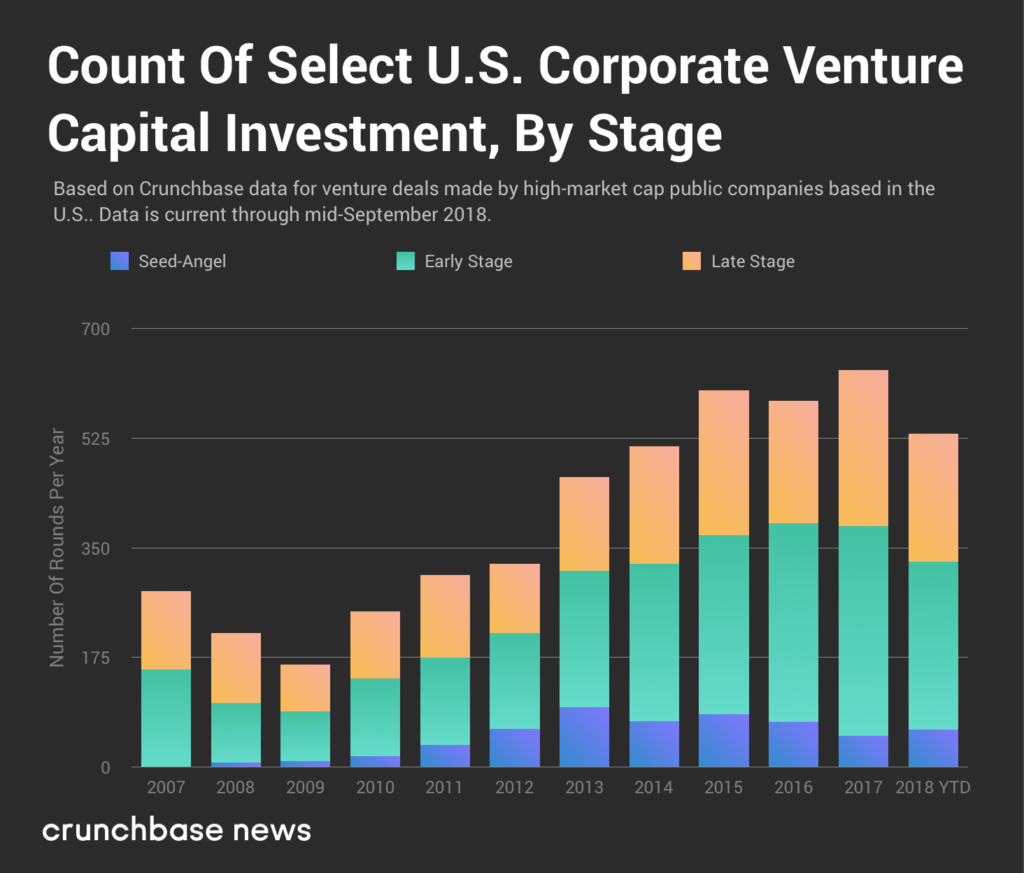

And 2018 is on track to set a record for U.S. corporate involvement in venture deals. We come to this conclusion after analyzing corporate venture investment patterns of the top 100 publicly traded, U.S.-based companies (as ranked by market capitalizations at time of writing). The chart below shows that investing activity, broken out by stage, for each year since 2007.

A few things stick out in this chart.

The number of rounds these big corporations invest in is on track to set a new record in 2018. Keep in mind that there’s a little over one full quarter left in the year. And although the holidays tend to bring a modest slowdown in venture activity over time, there’s probably sufficient momentum to break prior records.

The other thing to note is that our subset of corporate investors have, over time, made more investments in seed and early-stage companies. In 2018 to date, seed and early-stage rounds account for over 60 percent of corporate venture deal flow, which may creep up as more rounds get reported. (There’s a documented reporting lag in angel, seed, and Series A deals in particular.) This is in line with the past couple of years.

Finally, we can view this chart as a kind of microcosm for blue-chip corporate risk attitudes over the past decade. It’s possible to see the fear and uncertainty of the 2008 financial crisis causing a pullback in risk capital investment.

Even though the crisis started in 2008, the stock market didn’t bottom out until 2009. You can see that bottom reflected in the low point of corporate venture investment activity. The economic recovery that followed, bolstered by cheap interest rates that ultimately yielded the slightly bloated and strung-out market for both public and private investors? We’re in the thick of it now.

Whereas most traditional venture firms are beholden to their limited partners, that investor base is often spread rather thinly between different pension funds, endowments, funds-of-funds, and high-net-worth family offices. With rare exception, corporate venture firms have just one investor: the corporation itself.

More often than not, that results in corporate venture investments being directionally aligned with corporate strategy. But corporations also invest in startups for the same reason garden-variety venture capitalists and angels do: to own a piece of the future.

A note on data

Our goal here was to develop as full a picture as possible of a corporation’s investing activity, which isn’t as straightforward as it sounds.

We started with a somewhat constrained dataset: the top 100 U.S.-based publicly traded companies, ranked by market capitalization at time of writing. We then traversed through each corporation’s network of sub-organizations as represented in Crunchbase data. This allowed us to collect not just the direct investments made by a given corporation, but investments made by its in-house venture funds and other subsidiaries as well.

It’s a similar method to what we did when investigating Alphabet’s investing universe. Using Alphabet as an example, we were able to capture its direct investments, plus the investments associated with its sub-organizations, and their sub-organizations in turn. Except instead of doing that for just one company, we did it for a list of 100.

This is by no means a perfect approach. It’s possible that corporations have venture arms listed in Crunchbase, but for one reason or another, the venture arm isn’t listed as a sub-organization of its corporate parent. Additionally, since most of the corporations on this list have a global presence despite being based in the United States, it’s likely that some of them make investments in foreign markets that don’t get reported.

Source: Tech Crunch