“Welcome to the United States of America.”

That’s the first thing you read when you find out your green card application was approved. Those long-awaited words are printed on fancier-than-usual paper, an improvement on the usual copy machine printed paper that the government sends to periodically remind you that you, like millions of other people, are stuck in the same slow bureaucratic system.

First you cry — then you cry a lot. And then you celebrate. But then you have to wait another week or so for the actual credit card-sized card — yes, it’s green — to turn up in the mail before it really kicks in.

It took two years to get my green card, otherwise known as U.S. permanent residency. That’s a drop in the ocean to the millions who endure twice, or even three times as long. After six years as a Brit in New York, I could once again leave the country and arrive without worrying as much that a grumpy border officer might not let me back in because they don’t like journalists.

The reality is, U.S. authorities can reject me — and any other foreign national — from entering the U.S. for almost any reason. As we saw with President Trump’s ban on foreign nationals from seven Muslim-majority nations — since ruled unconstitutional — the highly vetted status of holding a green card doesn’t even help much. You have almost no rights and the questioning can be brutally invasive — as I, too, have experienced before, along with the stare-downs and silent psychological warfare they use to mentally shake you down.

I was curious what they knew about me. With my green card in one hand and empowered by my newfound sense of immigration security, I filed a Freedom of Information request with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to obtain all of the files the government had collected on me in order to process my application.

Seven months later, disappointment.

USCIS sent me a disk with 561 pages of documents and a cover letter telling me most of the interesting bits were redacted, citing exemptions such as records relating to officers and government staff, investigatory material compiled for law enforcement purposes, and techniques used by the government to decide an applicant’s case.

But I did get almost a decade’s worth of photos taken by border officials entering the United States.

Seven years of photos taken at the U.S. border. (Source: Homeland Security/FOIA)

What’s interesting about these encounters is that you can see me getting exponentially fatter over the years while my sense of style declines at about the same rate.

Each photo comes with a record from a web-based system called the Customer Profile Management Service (CPMS), which stores all the photos of foreign nationals visiting or returning to the U.S. from a camera at port of entries.

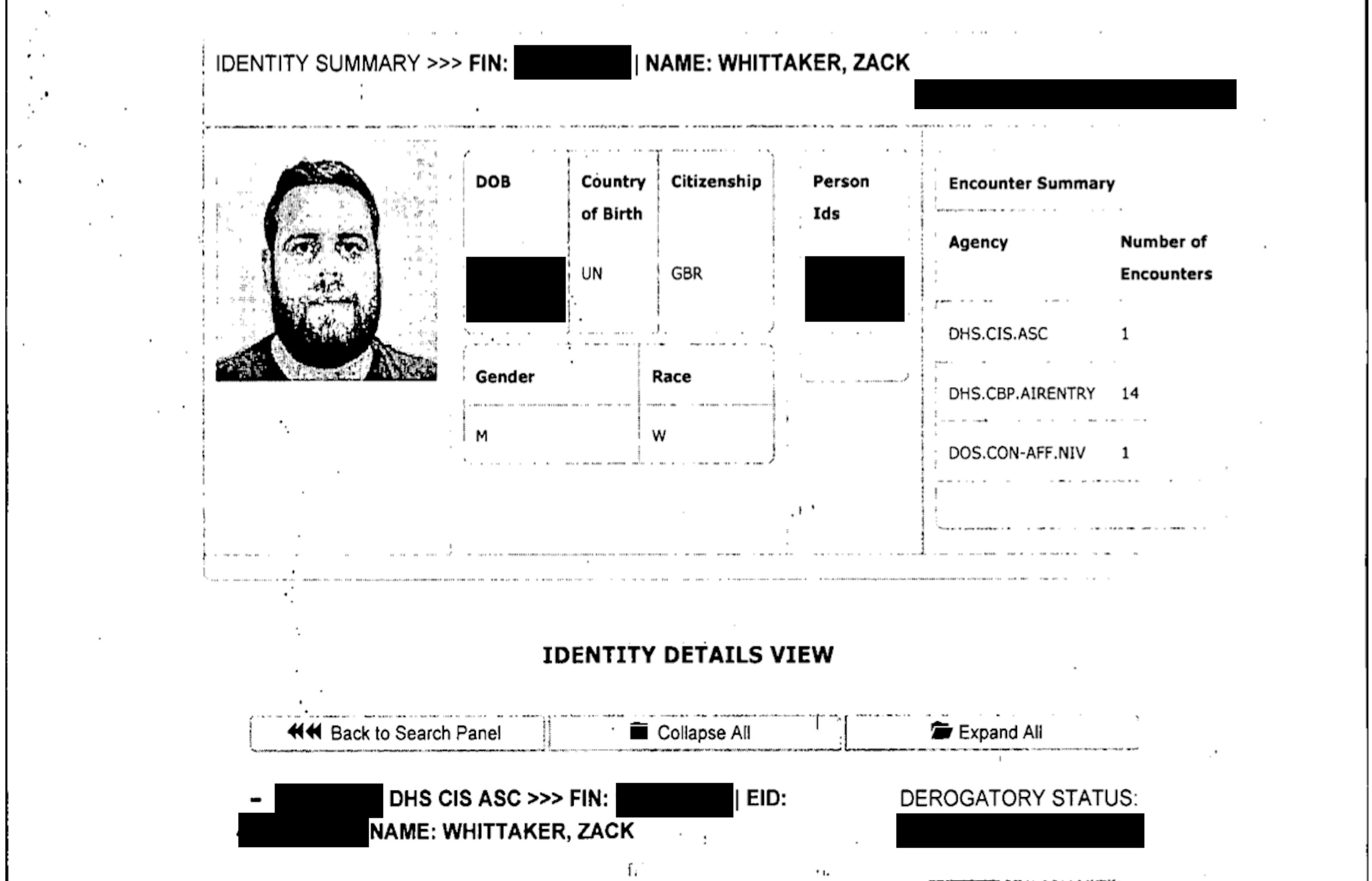

Immigration officers and border officials use the Identity Verification Tool (IVT) to visually confirm my identity and review my records at the border and my interview, as well as checking for any “derogatory” information that might flag a problem in my case.

The government’s IDENT system, which immigration staff and border officials use to visually verify an applicant’s identity along with any potentially barring issues, like a criminal record. (Source: FOIA)

Everyone’s file will differ, and my green card case was somewhat simple and straightforward compared to others.

Some 90 percent of my file are things my lawyer submitted — my application, my passport and existing visa, my bank statements and tax returns, my medical exam, and my entire set of supporting evidence — such as my articles, citations, and letters of recommendation. The final 10 percent were actual responsive government documents, and some random files like photocopied folders.

And there was a lot of duplication.

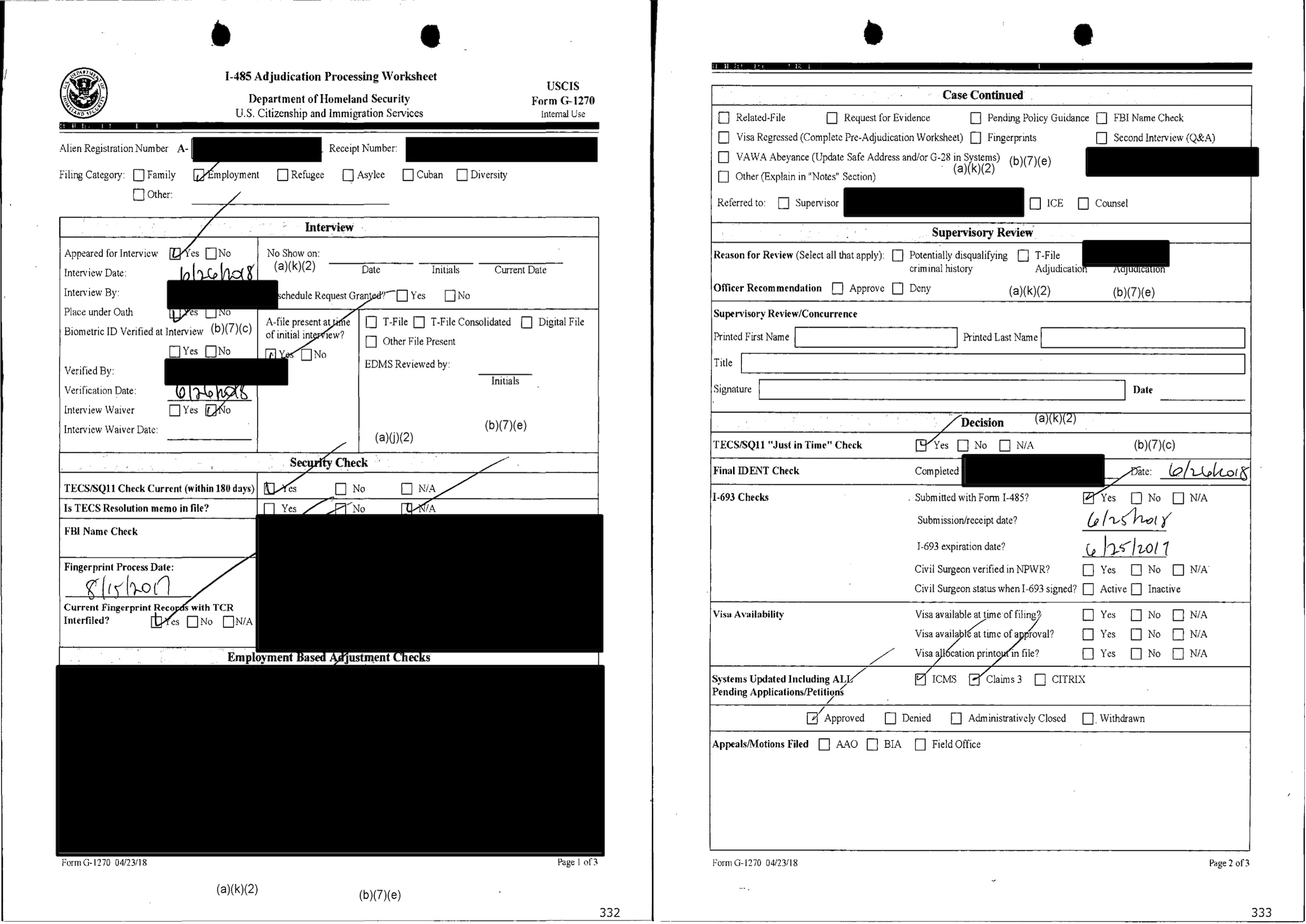

From the choice files we are publishing, the green card process appears highly procedural and offered little to nothing in terms of decision making by immigration officers. Many of the government-generated documents were mostly box-ticking exercises, such as verifying the authenticity of documents along the chain of custody. A single typo can derail an entire case.

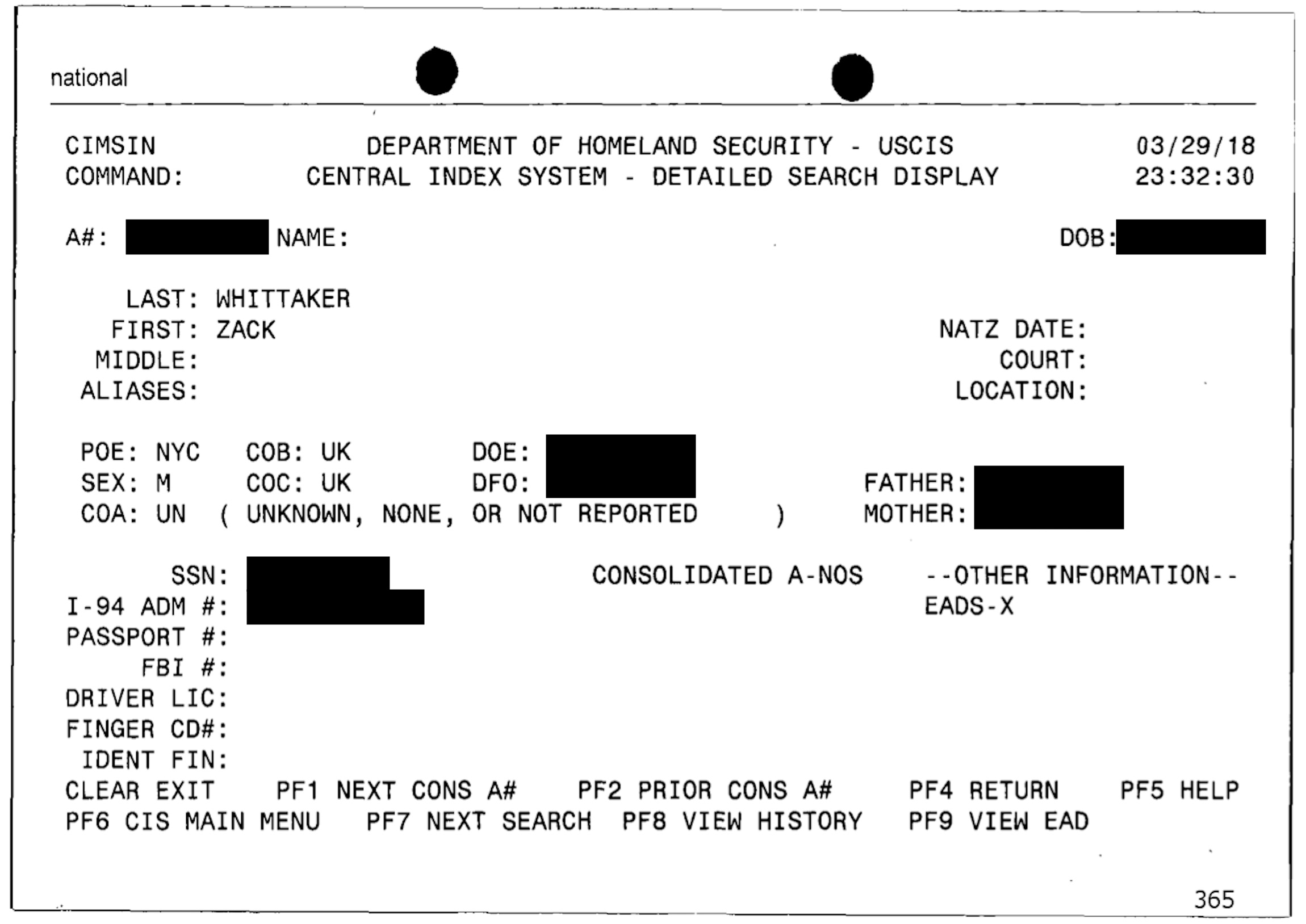

The government uses several Homeland Security systems to check my immigration records against USCIS’ Central Index System, and verifying my fingerprints against my existing records stored in its IDENT system to ensure it’s really me at the interview.

USCIS’ Central Index System, a repository of data held by the government as applications go through the immigration process. (Source: FOIA)

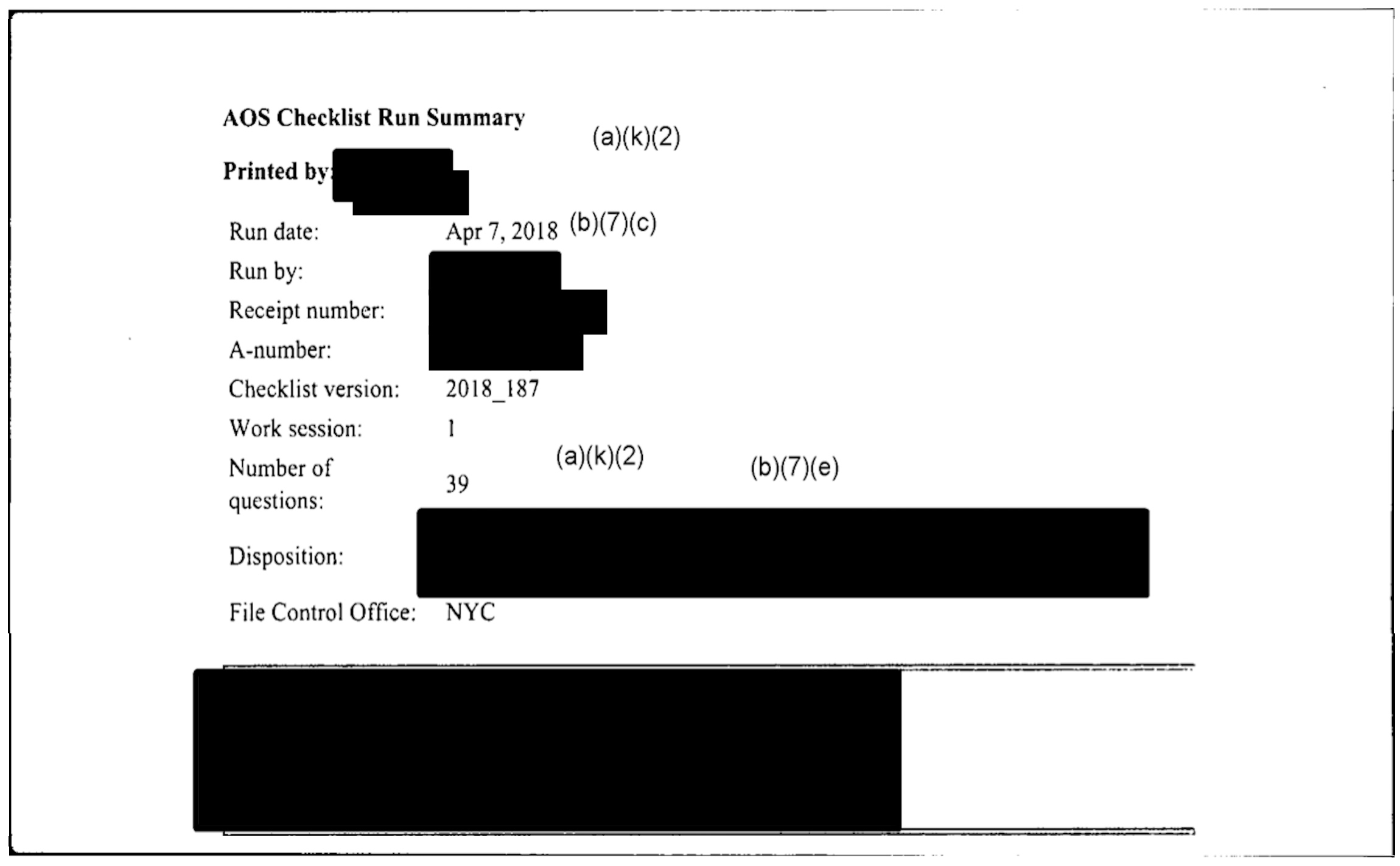

During my adjustment-of-status interview with an immigration officer, my “disposition” was recorded but redacted. (Spoiler alert: it was probably “sweaty and nervous.”)

A file filled out by an immigration officer at an adjustment of status interview, which green card candidates are subject to. (Source: FOIA)

Following the interview, the immigration officer checks to make sure that the interview procedures are properly carried out. Homeland Security also pulls in data from the FBI to check to see if my name is on a watchlist, but also to confirm my identity as the real person applying for the green card.

And, in the end, two years of work and waiting came down to was a single checked box following my interview. “Approved.”

The final adjudication of an applicant’s green card. (Source: FOIA)

It’s no secret that you can FOIA for your green card file. Some are forced to file to obtain their case files in order to appeal their denied applications.

Runa Sandvik, a senior director of information security at The New York Times, obtained her border photographs from Homeland Security some years ago. Nowadays, it’s just as easy to request your files. Fill out one form and email it to the USCIS.

For me, next stop is citizenship. Just five more years to go.

Read more:

- Trump administration sued over warrantless smartphone searches at US borders

- Border agents can’t lawfully search data stored in the cloud

- The startup community must defend merit-based immigration

- A simple data analysis disproves the argument for building a border wall

- The startup community must defend merit-based immigration

- The hottest new space to disrupt is immigration

- Why Silicon Valley needs more visas

Source: Tech Crunch